This is the multi-page printable view of this section. Click here to print.

News About Kubernetes

- Fault Tolerance Solutions for Multi-Cluster Kubernetes: Part 1

- Rootless container builds on Kubernetes

- autofs in containers

- GitLab Runners and Kubernetes: A Powerful Duo for CI/CD

- Nurturing Sustainability: Raising Power Consumption Awareness

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 6

- Webinar: Fully Automated Deployments with ArgoCD

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 5

- Webinar: Container Storage Improved: What's New in CVMFS and EOS Integrations

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 4

- Propagating OAuth2 tokens made easier

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 3

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 2

- Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 1

- Announcing CVMFS CSI v2

- A Summer of Testing and Chaos

- Summary of the GitOps Workshop

- GitOps Workshop

- Kubernetes Deprecations and Removals v1.20/21/22

Fault Tolerance Solutions for Multi-Cluster Kubernetes: Part 1

Supervisor: Jack Munday

My summer at CERN OpenLab

This summer I had the opportunity to work as a summer student at CERN OpenLab, where I was part of the IT-CD team. My project focused on implementing fault tolerance solutions for multi-cluster Kubernetes deployments, specifically using Cilium Cluster Mesh and various database technologies. The goal was to ensure high availability and redundancy for user traffic and databases across multiple clusters.

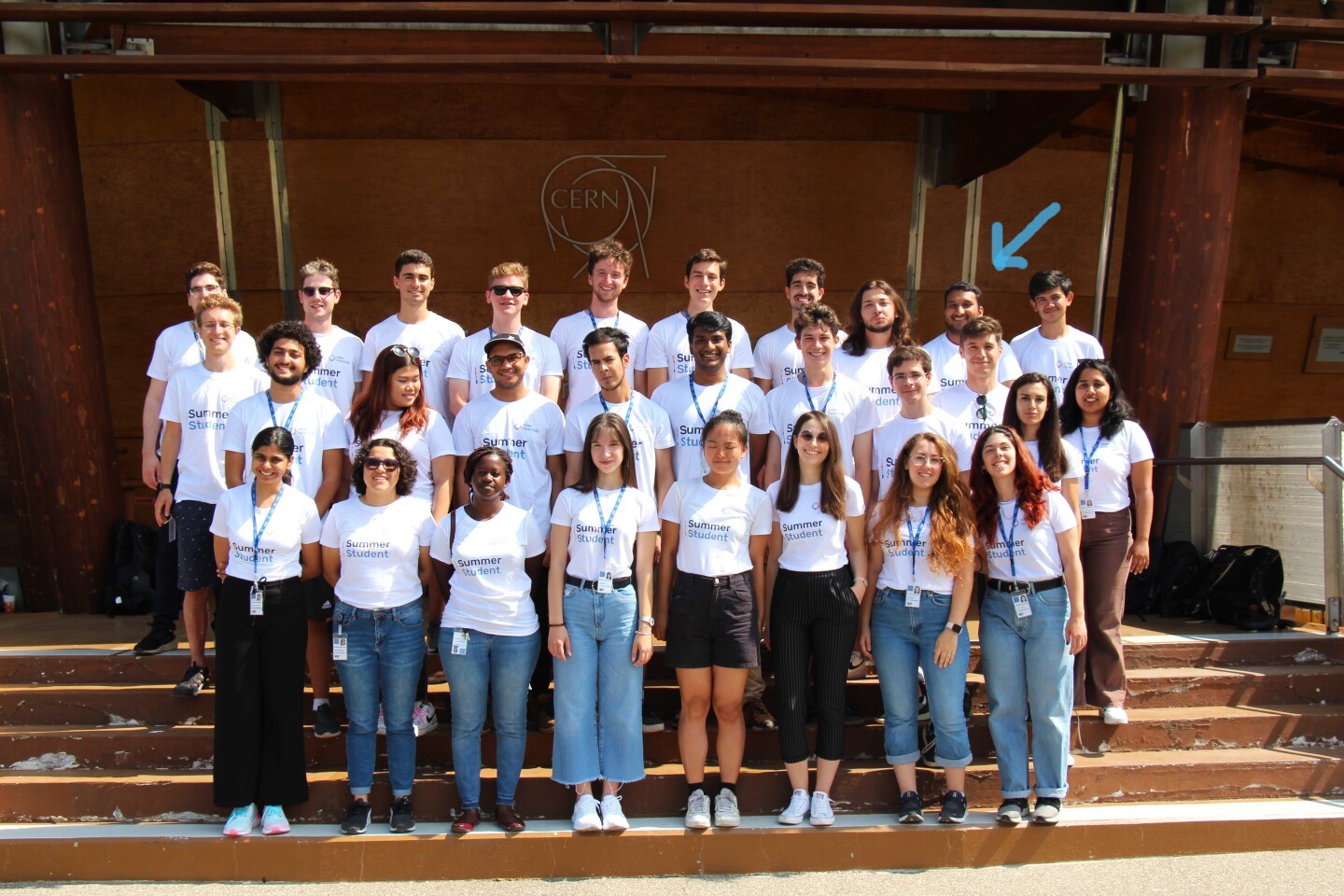

I had a great summer at CERN, I learnt a lot both professionally and personally, and I had the chance to meet many interesting people. Without further a do, let’s go into it!

OpenLab Summer Students class of 2025.

Introduction

High Availability is the design of systems and services to ensure they remain operation and accessible with minimal downtime, even in the face of server failures. It is a broader field of Business Continuity, which is a set of strategies to keep business operations during and after disruptions. The four levels of Business Continuity are described in the diagram below. The levels go from Cold with hours or even days of downtime, to Active-Active with practically no downtime.

Levels of Business Continuity. Inspired by CERN’s BC/DR Team.

In these two articles, we will focus on Active-Active and Active-Passive levels. Active-Active is a configuration where multiple clusters are running the same application simultaneously, sharing the load and providing redundancy. Active-Passive is a configuration where one cluster is active and serving requests, while another cluster is on standby, ready to take over in case of failure. In the context of this article, Active-Passive only provides redundancy for databases, which are continuously replicated across clusters. In the table above, the Active-Passive covers all the levels before Active-Active. The second article is about Active-Passive and is released on this same blog.

Active-Active Setup for Applications

Cilium is a Kubernetes CNI (Container Network Interface) plugin that provides advanced networking and security features for Kubernetes clusters. It is designed to enhance the performance, scalability, and security of containerized applications. Cilium uses eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) technology to implement networking and security policies at the kernel level, allowing for efficient and flexible network management.

Cilium Cluster Mesh is a feature that allows multiple Kubernetes clusters to be connected and managed as a single logical network. This enables seamless communication between pods across different clusters. Cluster Mesh is particularly useful for multi-cluster deployments, where applications need to span multiple clusters for high availability. This feature differs from service mesh, which is a layer that provides communication between services within a cluster, whereas Cluster Mesh focuses on communication between clusters.

The benefit of Cilium Cluster Mesh is that it allows for seamless communication between pods across different clusters, enabling load balancing and failover capabilities. It allows user traffic to be distributed across multiple clusters, ensuring that if one cluster fails, the other clusters can continue to serve requests. Furthermore, with Cilium Cluster Mesh it is seamless to label services as global, which allows them to be discovered and accessed from any cluster in the mesh. This way it is also easy to group pods together, as the pods with the same names in different groups perform the load balancing just between each other.

This chapter will cover the setup of Cilium Cluster Mesh for Active-Active user traffic. The setup involves configuring multiple pods in different clusters, and then load balancing the traffic across these pods. The goal is to ensure that user requests are distributed evenly across the clusters, providing redundancy and high availability even if one of the clusters fail. The diagram below illustrates the architecture used for this setup, with the API- and ML-services running in different clusters, and the user traffic being load balanced across them pairwise.

Cilium Cluster Mesh architecture.

Cilium Cluster Mesh Basic Installation

Installing Cilium and Cilium Cluster Mesh is straightforward with the Cilium CLI, and you can follow this guide by Cilium to get it installed.

However, users may encounter issues with the Cilium Cluster Mesh installation via Cilium CLI, especially if they have a larger umbrella Helm chart for all their installations. Furthermore, when running the cilium clustermesh connect command on the CLI installation, the Cilium installation exceeded Helm release size limit of 1 MB. To overcome this, one can install Cilium Cluster Mesh manually with Helm. Let’s assume that one has two clusters named cilium-001and cilium-002, both with certmanager installed. On a high level, it can be done as follows:

- Create the Kubernetes clusters and install Cilium in them via Helm.

# Run this against both of the Kubernetes clusters.

helm repo add cilium https://helm.cilium.io/

helm install -n kube-system cilium cilium/cilium --create-namespace --version 1.18.0

- We ran multiple helm upgrades to register and mesh our clusters together. First installing cilium with

clustermesh.useAPIServer=trueand then enablingclustermeshin a subsequent upgrade with the relevant configuration for all clusters. Below is presented the final configuration for brevity for cilium-002, the configuration for cilium-001 is similar with a different CIDR range and the certificates for cilium-002 instead.

---

# cilium-002.yaml

cilium:

cluster:

name: <CILIUM-002-MASTER-NODE-NAME> # Master node name from `kubectl get no`

id: 002 # Cluster ID, can be any number, but should be unique across clusters.

ipam:

operator:

clusterPoolIPv6MaskSize: 120

clusterPoolIPv4MaskSize: 24

clusterPoolIPv6PodCIDRList:

- 2001:4860::0/108

clusterPoolIPv4PodCIDRList: # Ensure each cluster in your mesh uses a different CIDR range.

- 10.102.0.0/16

bpf: # Mandatory to fix issue mentioned in https://github.com/cilium/cilium/issues/20942

masquerade: true

clustermesh:

apiserver:

tls:

server:

extraDnsNames:

- "*.cern.ch" # If you are relying on cilium to generate your certificates.

useAPIServer: true

config:

enabled: true

domain: cern.ch

clusters:

- name: <CILIUM-001-MASTER-NODE-NAME> # Second cluster master node name from kubectl get no.

port: 32379

ips:

- <CILIUM-001-MASTER-NODE-IP> # Second cluster internal IP address from kubectl get no -owide.

tls: # Certificates can be retrieved with `kubectl get secret -n kube-system clustermesh-apiserver-remote-cert -o jsonpath='{.data}'`

key: <APISERVER-KEY>

cert: <APISERVER-CERT>

caCert: <APISERVER-CA-CERT>

Load Balancer Setup

To enable external access to the cluster with this integration, an ingress must be deployed, which in turn automatically provisions a load balancer for the cluster. Ingress-nginx ingress controller is used for this purpose, as with Cilium ingress controller I encountered problems with the cluster networking (see more in the Troubleshooting section). Install the ingress-nginx controller with the following Helm configuration:

# cilium-002-ingress-controller.yaml

ingress-nginx:

controller:

nodeSelector:

role: ingress

service:

enabled: true

nodePorts:

http: ""

https: ""

type: LoadBalancer

enabled: true

Since the Helm configuration deployed the load balancer into a node with label ingress, we should label one as such, preferably before the ingress-nginx installation:

kubectl label node <NODE-OF-CHOICE> role=ingress

Next up, we should deploy the ingress and thus the load balancer by applying this custom resource definition (CRD):

# ingress-manifest.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: sample-http-ingress

annotations:

# This annotation added to get the setup to work

# Read more at https://github.com/cilium/cilium/issues/25818#issuecomment-1572037533

# and at https://github.com/kubernetes/ingress-nginx/blob/main/docs/user-guide/nginx-configuration/annotations.md#service-upstream

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/service-upstream: "true"

spec:

ingressClassName: nginx

rules:

- host:

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: api-service # Name of a global service backend. If you would deploy another service, you would need to change this name to ML-service or something else.

port:

number: 8080

Deploy this CRD with kubectl apply -f ingress-manifest.yaml. The load balancer will be provisioned automatically, and the ingress controller will start routing traffic to the specified backend service later. Apply this in both clusters. Then, configure DNS load balancing by assigning the same DNS name to the external addresses of both load balancers. This way, when clients resolve the DNS name, the DNS service distributes requests across the available load balancers. This step depends on the DNS service you are using.

Global Services

The automatic load-balancing between clusters can be achieved by defining Kubernetes ClusterIP services with identical names and namespaces and by adding the annotation service.cilium.io/global: "true" to declare them global. Cilium will take care of the rest. Furthermore, since this guide is utilizing an external ingress controller, an additional annotation is needed for the global services, namely service.cilium.io/global-sync-endpoint-slices: "true". Apply the following CRD in both of the clusters to create the global service ClusterIP, and mock pods within them:

# global-api-service-manifest.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

# The name and namespace need to be the same across services in different clusters. This name is important as it defines the load balancing groups for Cilium.

name: api-service

annotations:

# Declare the global service.

# Read more here: https://docs.cilium.io/en/stable/network/clustermesh/services/

service.cilium.io/global: "true"

# Allow the service discovery with third-party ingress controllers.

service.cilium.io/global-sync-endpoint-slices: "true"

spec:

type: ClusterIP

ports:

- name: http

protocol: TCP

port: 8080

targetPort: 80

selector:

app: api-service

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: api-service

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: api-service

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: api-service

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx

ports:

- containerPort: 80

volumeMounts:

- name: html

mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html/index.html

subPath: index.html

volumes:

- name: html

configMap:

name: custom-index-html

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: custom-index-html

data:

# Hello from Cluster 001 or Cluster 002, depending on the cluster.

index.html: |

Hello from Cluster 00x

Deploy with kubectl apply -f global-api-service-manifest.yaml, after which one can check that the global service is working by checking that we can get responses from both of the clusters:

# Run a pod which can access the cluster services.

kubectl run curlpod --rm -it --image=busybox -- sh

# This should return "Hello from Cluster 001" or "Hello from Cluster 002" depending on which cluster the request was routed to.

wget -qO- http://api-service:8080

Testing Cluster Mesh Connectivity

Now everything should be working. You can test the solution in many ways, below listed a couple methods:

- By using Cilium CLI (needs Cilium CLI installed):

# To check that normal Cilium features are working. cilium status # Expected output /¯¯\ /¯¯\__/¯¯\ Cilium: OK \__/¯¯\__/ Operator: OK /¯¯\__/¯¯\ Envoy DaemonSet: OK \__/¯¯\__/ Hubble Relay: OK \__/ ClusterMesh: OK DaemonSet cilium Desired: 2, Ready: 2/2, Available: 2/2 DaemonSet cilium-envoy Desired: 2, Ready: 2/2, Available: 2/2 Deployment cilium-operator Desired: 2, Ready: 2/2, Available: 2/2 Deployment clustermesh-apiserver Desired: 1, Ready: 1/1, Available: 1/1 Deployment hubble-relay Desired: 1, Ready: 1/1, Available: 1/1 Deployment hubble-ui Desired: 1, Ready: 1/1, Available: 1/1 Containers: cilium Running: 2 cilium-envoy Running: 2 cilium-operator Running: 2 clustermesh-apiserver Running: 1 hubble-relay Running: 1 hubble-ui Running: 1 Cluster Pods: 27/27 managed by Cilium Helm chart version: 1.17.5 Image versions cilium quay.io/cilium/cilium:v1.17.5 2 cilium-envoy quay.io/cilium/cilium-envoy:v1.32.7 2 cilium-operator quay.io/cilium/operator-generic:v1.17.5 2 clustermesh-apiserver quay.io/cilium/clustermesh-apiserver:v1.17.5 3 hubble-relay quay.io/cilium/hubble-relay:v1.17.5 1 hubble-ui quay.io/cilium/hubble-ui-backend:v0.13.2 1 hubble-ui quay.io/cilium/hubble-ui:v0.13.2@sha256 1# To check if Cluster Mesh installation is working. You can run this both on cilium-001 and cilium-002 clusters, and the output should be similar in both. Example ran on cilium-001. cilium clustermesh status # Expected output ⚠️ Service type NodePort detected! Service may fail when nodes are removed from the cluster! ✅ Service "clustermesh-apiserver" of type "NodePort" found ✅ Cluster access information is available: - <CILIUM-001-MASTER-IP>:32379 ✅ Deployment clustermesh-apiserver is ready ℹ️ KVStoreMesh is enabled ✅ All 2 nodes are connected to all clusters [min:1 / avg:1.0 / max:1] ✅ All 1 KVStoreMesh replicas are connected to all clusters [min:1 / avg:1.0 / max:1] 🔌 Cluster Connections: - <CILIUM-002-MASTER-NODE-NAME>: 2/2 configured, 2/2 connected - KVStoreMesh: 1/1 configured, 1/1 connected 🔀 Global services: [ min:1 / avg:1.0 / max:1 ]# To test the Cluster Mesh connection. # Assumes that you have set up kubectl contexts for the clusters. # To test the Cluster Mesh pod connectivity. cilium connectivity test --context <CLUSTER-1-CTX> --destination-context <CLUSTER-2-CTX> - Verifying that you can see pods with identities in both clusters:

kubectl exec -it -n kube-system $(kubectl get pods -n kube-system -l k8s-app=cilium -o jsonpath='{.items[0].metadata.name}') -c cilium-agent -- cilium-dbg node list | awk '{print $1}'

Name

cilium-001-master-0/cilium-001-master-0

cilium-001-master-0/cilium-001-node-0

cilium-002-master-0/cilium-002-master-0

cilium-002-master-0/cilium-002-node-0

- By curling ingress-nginx load balancer with load balancer IP or DNS:

# Run either one of these two to get the IP. kubectl get ingress sample-http-ingress -o yaml openstack loadbalancer list # Use either IP or DNS to curl the system. curl <DNS-NAME> -v curl http://<LB-IP>:8080 -v # Expected output: # Hello from Cluster 001 # Hello from Cluster 002

The Cluster Mesh connectivity refers to the ability of Cilium to route requests to pods in both clusters. It works non-deterministically, and if a pod in the local or remote cluster breaks, the requests are routed to the working cluster.

The failover was tested by downscaling the replicas of the API-service in one cluster, and then checking that the requests were routed to the other cluster. The failover worked as expected, and the requests were routed to the working cluster.

Troubleshooting

bpf.masquerade=truein the Cilium Helm configuration is required as stated here.- Cilium also offers an ingress controller. I experimented with it with the following YAML:

However, I encountered issues with the cluster networking, and it did not work as expected. I was able to query the ingress controller from within the cluster, but when I tried to enable the host network and query the node IP address, I did not get a response. Cilium ingress controller did not require the

bpf: masquerade: false ingressController: enabled: true hostNetwork: enabled: true nodes: matchLabels: role: ingress sharedListenerPort: 8010 service: externalTrafficPolicy: null type: ClusterIPservice.cilium.io/global-sync-endpoint-slices: "true"annotation, as it is already integrated with Cilium Cluster Mesh.

Next Up

In the next article, I will cover the Active-Passive setup for databases, we will cover setting up PostgreSQL, Valkey and OpenSearch with multi-cluster data replication. The goal is to ensure that databases are continuously replicated across clusters, providing redundancy and high availability in case of cluster failures.

References

Rootless container builds on Kubernetes

An important task in most teams’ pipelines is building container images. Developers need their builds to be fast, reproducible, reliable, secure and cost-effective. The most isolated setup one can have in a cloud environment is running builds in an isolated server physical or virtual. Spinning new virtual machines (or physical in some cases) is quite easy in cloud environments, but it adds a lot of overhead, provisioning, monitoring, resource usage etc. On the other hand, running builds on a shared host can be insecure in non-trusted environments. Traditionally, dockerd had to be run as root or with root privileges and access to the docker socket was the same as being root. Podman had the same requirements initially as well. In a shared environment (a shared linux host), the most secure option is to run everything as non-root, for additional isolation user namespaces can also be used.

“In Kubernetes v1.33 support for user namespaces is enabled by default!”, this was a big announcement from the cloud-native community earlier this year. Not just because of the feature availability, it has been in beta since v1.30, but because of the maturity of the tooling around it. Improvements had to be made in the Linux Kernel, containerd, cri-o, runc, crun and Kubernetes itself. All this work improved the capabilities of these tools to run workloads rootless.

In this post, we will present 3 options (podman/buildah, buildkit and kaniko) for building container images in Kubernetes pods as non-root with containerd 2.x as runtime. Further improvements can be made using kata-containers, firecracker, gvisor or others but the complexity increases and administrators have to maintain multiple container runtimes.

Podman and Buildah

Podman is a tool to manage OCI containers and pods. Buildah is a tool that facilitates building Open Container Initiative (OCI) container images. Podman vendors buildah’s code for builds, so we can consider it the same. Both CLIs resemble the docker build CLI, and they can be used as drop-in replacements in existing workflows.

To run podman/buildah in a pod we can create an emptyDir volume to use for storage and set a limit to it and also point the run root directory to that volume as well. Then we can runAsUser 1000 (the podman/buildah user in the respective images).

Here is the storage configuration (upstream documentation: storage.conf):

[storage]

driver = "overlay"

runroot = "/storage/run/containers/storage"

graphroot = "/storage/.local/share/containers/storage"

rootless_storage_path = "/storage/.local/share/containers/storage"

[storage.options]

pull_options = {enable_partial_images = "true", use_hard_links = "false", ostree_repos=""}

[storage.options.overlay]

For both buildah and podman we need to configure storage with the overlay

storage driver for good performance. vfs is also an option (driver = "vfs")

but it is much slower especially for big images. Linked are the full manifests

for buildah and podman.

We need the following options:

- place storage.conf in

/etc/containers/storage.confor~/.config/containers/storage.confand mount an emptyDir volume in/storage, we can also configure a size limit... volumeMounts: - name: storage mountPath: /storage - name: storage-conf mountPath: /etc/containers/ volumes: - name: storage emptyDir: sizeLimit: 10Gi - name: storage-conf configMap: name: storage-conf - disable host users to enable user namespaces and run as user

1000... spec: hostUsers: false containers: - name: buildah securityContext: runAsUser: 1000 runAsGroup: 1000 ... - finally build with:

buildah/podman build -t example.com/image:dev .

Buildkit

Buildkit is a project responsible for building artifacts and it’s the project behind the docker build command for quite some time. If you’re using a recent docker you are already using buildkit. docker buildx is a CLI plugin to add extended build capabilities with BuildKit to the docker CLI. Apart from the docker CLI, buildctl and nerdctl can be used against buildkit.

Here is the full example with buildkit based on the upstream example.

To build with buildkit we need to:

- use the buildkit image

docker.io/moby/buildkit:masteror pin to a version egdocker.io/moby/buildkit:v0.23.1 - mount a storage volume (similar to buildah/podman) and specify the storage

directory

BUILDKITD_FLAGS="--root=/storage"... volumeMounts: - name: storage mountPath: /storage volumes: - name: storage emptyDir: sizeLimit: 10Gi - run privileged but with host users disabled

... spec: hostUsers: false containers: - name: buildkit securityContext: # privileged in a user namespace privileged: true ... - for standalone builds we can use buildctl-daemonless.sh a helper script

inside the image

buildctl-daemonless.sh \ build \ --frontend dockerfile.v0 \ --local context=/workspace \ --local dockerfile=/workspace

We can not use buildkit rootless with user namespaces, rootlesskit needs to be

able to create user mappings. User namespaces can be used with rootful

buildkit, where root is mapped to a high number user, so not really root or

privileged on the host. Here is the rootless upstream

example,

it needs --oci-worker-no-process-sandbox use the host PID namespace and procfs (WARNING: allows build containers to kill (and potentially ptrace) an arbitrary process in the host namespace).

Instead of using buildctl-daemonless.sh or just buildctl, the docker CLI can be used.

docker CLI full example:

cd /workspace

docker buildx create --use --driver remote --name buildkit unix:///path/to/buildkitd.sock

docker buildx build -t example.com/image:dev .

Kaniko

Kaniko is a tool to build container images from a Dockerfile, inside a container or Kubernetes cluster. Kaniko is stable for quite some time and works without any storage configuration in kubernetes pods. Recently the project was deprecated by Google, but Chainguard is stepping up to maintain it. The debug tags of kaniko’s image contain a shell which is handy for CI pipelines.

To build with kaniko we do not need to mount any volumes for storage. Here is the full example with kaniko.

/kaniko/executor \

--context /workspace \

--dockerfile Dockerfile \

--destination example.com/image:dev \

--no-push

Performance and resource consumption

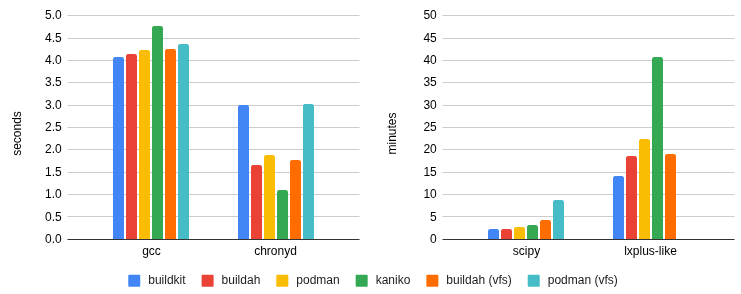

To compare the performance between all tools and try to spot differences, 4 build examples follow.

- gcc based on alpine:latest

- chronyd based on alpine, upstream project.

- jupyter notebook scientific python stack (scipy), upstream project.

- a CERN development environment based on Alma Linux (lxplus), which includes tools like: python, root.cern, HTcondor CLI, kubectl, helm, nvidia cuda toolkit, infiniband and others. Its size is ~35GB/20GB un/compressed, unfortunately it is an internal project.

The builds for gcc and chronyd take less than 5 seconds for all tools. Comparing resource consumption does not add any value. Especially for CIs, the build job may take longer to start or get scheduled.

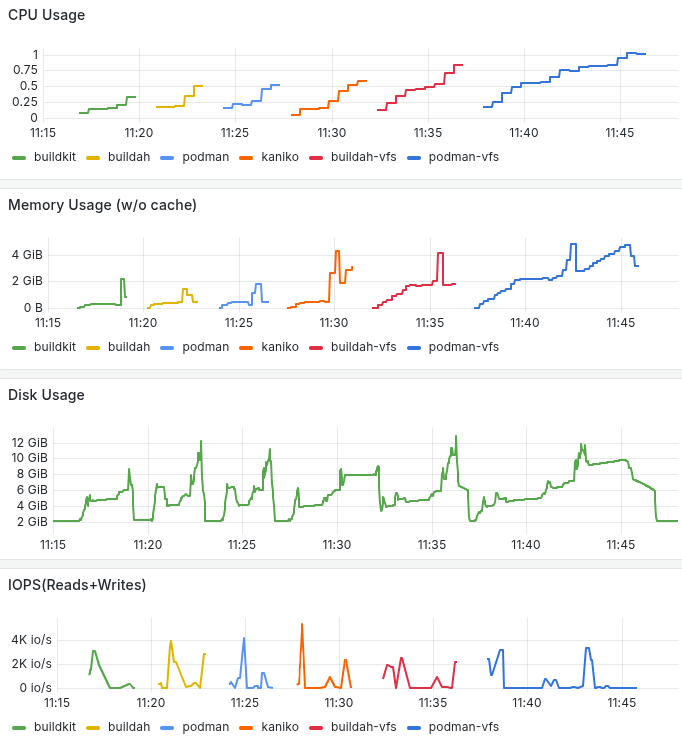

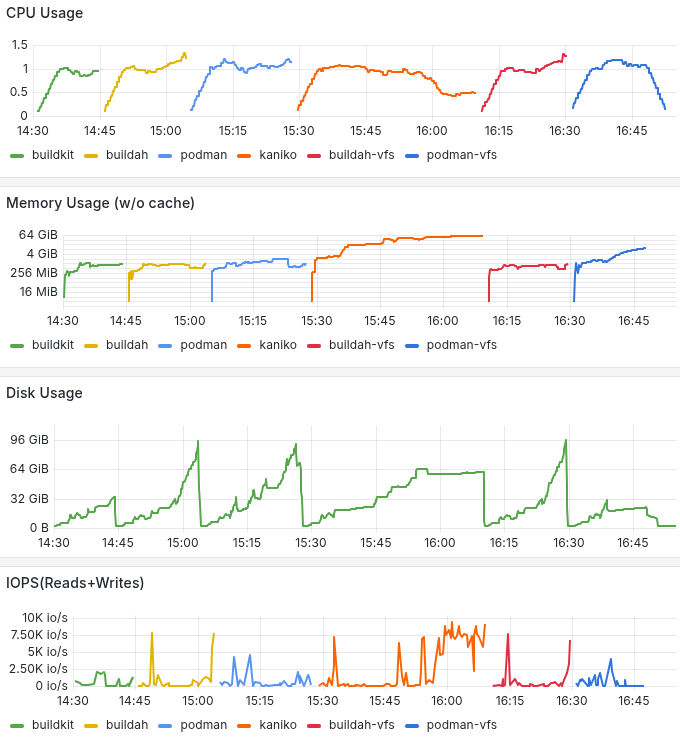

Moving on to build scipy and lxplus which are bigger images with a lot more files we start to see significant differences in build time and resource consumption. Buildkit and buildah/podman configured with overlayfs and overlay respectively, give faster build times, lower memory consumtion and better disk utilization. For the largest image, buildkit’s disk usage efficiency stands out. Below you can go through the build times and resource consumption based on kube-prometheus-stack.

Build time per experiment and per tool:

Pod resource consumption building scipy-notebook.

Pod resource consumption building CERN development environment.

Conclusion

With several improvements being done in past years, building containers as non-root has become much easier. All the mentioned tools provide similar functionality like caching. But which tool to choose?

- For all tools container images are available and good documentation is available.

- For most use cases, the build tool does not matter and the result is the same.

- Buildkit and buildah/podman are fast and do not consume a lot of resources (CPU/RAM). Kaniko has a different approach, for large images it may consume a lot of memory and it can be slower.

- Buildah/podman are daemonless and packages are available in most linux distributions and brew.

- In many open-source projects docker (with buildkit) is used to build images and downstream users may want to use the same workflow.

- Buildkit seems to be more efficient on disk usage for larger images.

Bonus: Caching

When it comes to building images in a CI (gitlab-ci/github/…) for incremental changes, similar to a local development machine, users may want to use caching and not build all layers in every push. Buildkit relies on an OCI artifact for caching while buildah/podman and kaniko need a repository. In a registry where multiple levels are allowed (eg example.com/project/repo/subrepo1/subrepo2), users can try to nest the cache in the same repository. If docker.io is your registry, you need a dedicated repo for caching.

buildkit:

buildctl build \

--export-cache type=registry,ref=example.com/image:v0.1.0-cache1 \

--import-cache type=registry,ref=example.com/image:v0.1.0-cache1 \

--output type=image,name=example.com/image:v0.1.0-dev1,push=false \

--frontend dockerfile.v0 \

--local context=. \

--local dockerfile=.

# buildctl-daemonless.sh accepts the same options

buildah/podman:

buildah build \

-t example.com/image:v0.1.0-dev1 \

--layers \

--cache-to example.com/image/cache \

--cache-from example.com/image/cache \

.

docker:

docker buildx build \

-t example.com/image:v0.1.0-dev1 \

--cache-from type=registry,ref=example.com/image:v0.1.0-cache1 \

--cache-to type=registry,ref=example.com/image:v0.1.0-cache1 \

--push \

.

# --push can be omitted

# --push is equivalent to --output type=image,name=example.com/image:v0.1.0-dev1,push=true \

kaniko:

/kaniko/executor \

--context $(pwd) \

--dockerfile Dockerfile \

--destination example.com/image:v0.1.0-dev1 \

--cache=true \

--no-push

# --cache-repo=example.com/image/cache inferred

autofs in containers

autofs handles on-demand mounting of volumes. This is crucial for some of our storage plugins, where it is not known which volumes a Pod will need during its lifetime.

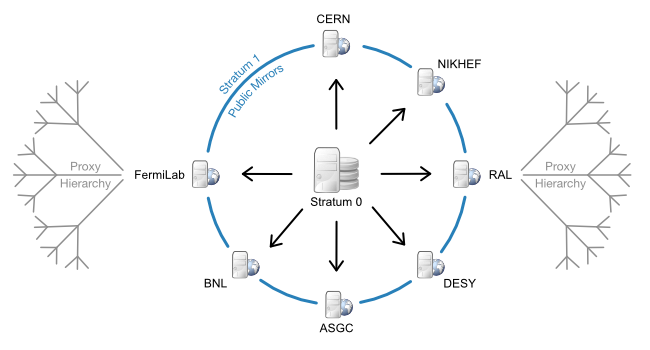

Container Storage Interface, CSI, is the industry standard for exposing storage to container workloads, and is the main way of integrating storage systems into Kubernetes. CSI drivers then implement this interface, and in our Kubernetes offerings we use it everywhere. In this blogpost we’ll discuss how we’ve made autofs work in eosxd-csi and cvmfs-csi drivers.

Motivation

Sometimes, it’s impractical if not impossible to say what volumes a Pod will need. Think Jupyter notebooks running arbitrary user scripts. Or GitLab runners. Our use cases involving access to storage systems whose different partitions, hundreds of them, can only be exposed as individual mounts. A good example of this is CVMFS, a software distribution service where each instance (repository) serving different software stacks is a separate CVMFS mount. And EOS with its many instances for different home directories and HEP experiments data falls into the same category.

autofs is a special filesystem that provides managed on-demand volume mounting and automatic unmounting after a period of inactivity. CSI drivers eosxd-csi and cvmfs-csi we use at CERN both rely on autofs to provide access to the many CVMFS repositories and EOS instances, and save on node resource utilization when these volumes are not accessed by any Pods at the moment.

Exposing autofs-based PVs

eosx-csi and cvmfs-csi implement almost identical setups in regards to how they expose autofs, and so we’ll focus on CVMFS only, and one can assume it works the same way for eosxd-csi too. While there may be other ways to make autofs work in containers, the findings listed here represent the current state of things and how we’ve dealt with the issues we’ve found along the way when designing these CSI drivers:

- how to run the automount daemon, and where,

- how to expose the autofs root so that it is visible to consumer Pods

- how to stop consumer Pods interfering with the managed mounts inside the autofs root

- how to restore mounts after Node plugin Pod restart.

Let’s go through each of them in the next couple of sections.

Containerized and thriving

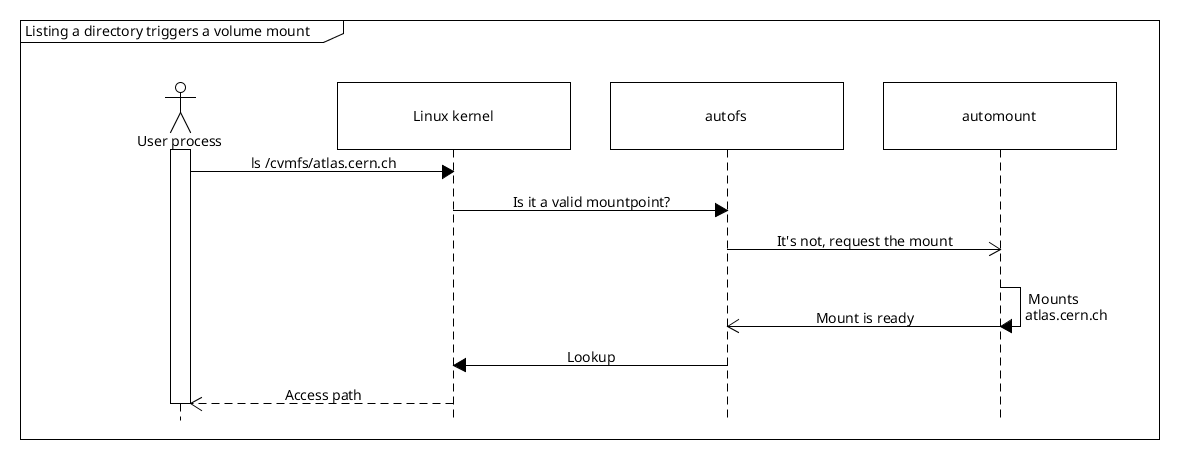

autofs relies on its user-space counterpart, the automount daemon, to handle requests to mount volumes and then resolve mount expirations when they haven’t been accessed for some time. To know where to mount what, users can define a set of config files, the so-called automount maps. They map paths on the filesystem to the mount command that shall be executed when the path is accessed. They are then read by the daemon to set everything up.

We run the automount daemon inside the CSI Node plugin Pods, as this gives us the ability to control how it is deployed and its lifetime. The maps are sourced into these Pods as a ConfigMap, leaving users and/or admins to supply additional definitions or change them entirely if they so wish. This is the indirect map we define for CVMFS:

/cvmfs /etc/auto.cvmfs

where /cvmfs marks the location where the daemon mounts the autofs root for this map entry. Then for any access in /cvmfs/<Repository>/... it runs the /etc/auto.cvmfs <Repository> executable. auto.cvmfs is a program that forms the mount command arguments. The automount daemon reads them, and runs the final mount <Arguments>, making the path /cvmfs/<Repository> available.

In summary, this is how cvmfs-csi initializes /cvmfs:

- A dedicated container in the Node plugin Pod runs

automount --foreground. With the process running in foreground it’s much easier to control its lifetime and capture its logs. - It waits until

/cvmfsis an autofs mountpoint (filesystem type0x0187). - It makes the autofs root shared with

mount --make-shared /cvmfs.

Node plugin needs to be run with hostPID: true, otherwise mount requests are not reaching the daemon:

# Running commands on the host node:

# * /var/cvmfs is the autofs root mountpoint (hostPath exposed to the Node plugin Pod).

# * The automount container runs in its own PID namespace.

# * Accessing /var/cvmfs/atlas.cern.ch does not trigger a mount in the automount daemon.

[root@rvasek-1-27-6-2-qqbsjsnaopix-node-0 /]# ls /var/cvmfs

[root@rvasek-1-27-6-2-qqbsjsnaopix-node-0 /]# ls /var/cvmfs/atlas.cern.ch

ls: cannot access '/var/cvmfs/atlas.cern.ch': No such file or directory

# Now, running automount in host's PID namespace.

[root@rvasek-1-27-6-2-qqbsjsnaopix-node-0 /]# ls /var/cvmfs/atlas.cern.ch

repo

Next, let’s see how we expose the autofs root to other Pods, in the context of a CSI Node plugin. Under the hood it’s all just bindmounts and mount sharing.

Sharing is caring, unless…

Let’s have a Pod that mounts a CVMFS PersistentVolume. As it gets scheduled on a node, kubelet invokes NodePublishVolume RPC on the cvmfs-csi Node plugin. The RPC’s request contains target_path: a hostPath where kubelet expects a new volume mount to appear, so that it can bind-mount it into the container that’s about to be started. This is where we expose the autofs root.

/cvmfs is made ready during Node plugin’s initialization (see above), so when a consumer Pod comes to the node, NodePublishVolume only needs to bind-mount the autofs root into the target_path:

mount --rbind --make-slave /cvmfs <Request.target_path>

-

--rbind: We use recursive mode because/cvmfsmay already contain mounts. Such situation is very common actually: first consumer Pod accesses/cvmfs/atlas.cern.ch; all consumers that come after must bindmount the inner mounts too. Otherwise they would show up only as empty directories, not being able to trigger autofs to mount them (because from automount’s point-of-view, the path and the mount already exists). -

--make-slave: We maketarget_patha one-way shared bindmount. There are a couple of reasons why it needs to be configured like that.By default, mountpoints are private. As such, one of the consequences is that if a new mount appears under the path, any later bindmounts of the path will not receive any (un)mount events. We need the mounts to be propagated though, otherwise if a Pod triggers a mount, it will not be able to access it.

Sharing the mountpoint both ways (with

--make-shared) would make events propagate correctly, and consumer Pods would see new inner mounts appear. But there is a catch: eventually the consumer Pods need to be deleted, triggering unmounts. The same event propagation that made inner mounts visible inside all of the bindmounts now starts working against us. Unmount events would propagate across all the bindmounts, attempting to unmount volumes not only for the Pod that was just deleted, but for all the consumer Pods. Clearly this is not something we want.To limit the blast radius of the events issued by unmounting

Request.target_path, we use slave mounts. They still receive events from the original autofs root, but when they themselves are unmounted, they don’t affect the root – it’s a one-way communication.

We have already touched on consumer Pod deletions and unmounts, but we haven’t described how is it actually done:

umount --recursive <Request.target_path>

--recursive: In general, when a Pod is deleted, its mounts need to be cleaned as well. kubelet invokesNodeUnpublishVolumeRPC on the Node plugin, unmounting the volume. In case of autofs, it’s not enough to justumount <Request.target_path>because the autofs root contains live mounts inside of it (see--rbindabove), and so this would fail withEBUSY. Instead,umount --recursiveneeds to be used.

One last thing to mention regarding unmounts is of course the mount expiry feature. We expose the inactivity timeout via a Helm chart variable, and admins can then configure its value. This didn’t need any specific setup on the CSI driver side, and so we’ll just mention what we’ve observed:

- mount expiry works well. Unmount events are correctly propagated to all slave mounts,

- when a mount expires, the automount daemon calls

umount --lazy, and so the actual unmount is deferred until there is nothing accessing it.

And lastly, consumer Pods need to set up their own mount propagation too, otherwise the events won’t be correctly propagated to the containers. This is easy enough to do:

spec:

containers:

- volumeMounts:

- name: cvmfs

mountPath: /cvmfs

mountPropagation: HostToContainer

...

This, in short, is all it took to run a basic autofs setup providing mount and unmount support for other Pods on the node. We’ve seen how cvmfs-csi starts the automount daemon, exposes the mountpoint(s) and how the consumers can let go of autofs-managed mounts when they are no longer needed. This all works great. In the next section we’ll describe what happens when the Node plugin Pod is restarted, and how we tackled the issues caused by that.

When things break

Pods can crash, get restarted, evicted. The age-old problem of persisting resources (in this case mounts) in ephemeral containers… If the Node plugin Pod goes down, so will the automount daemon that runs in it.

What can we do about it from within a CSI driver? Articles “Communicating with autofs” and “Miscellaneous Device control operations for the autofs kernel module” at kernel.org discuss autofs restore in great detail, but in short, the daemon must reclaim the ownership of the autofs root in order to be able to handle autofs requests to mount and unmount again. This is something that is supported out-of-the-box, however getting it to work in containers did not go without issues:

- automount daemon cleans up its mounts when exitting,

/dev/autofsmust be accessible,- autofs root must be exposed on the host so that it survives container restarts.

Let’s go through these one by one. We’ve mentioned that the automount daemon needs to be able to reclaim the autofs root. Under normal circumstances, once you ask the daemon to quit, it cleans up after itself and exists as asked. Cleaning up entails unmounting the individual inner mounts, followed up by unmounting the autofs root itself (analogous to umount --recursive /cvmfs). Now, one might ask how is the daemon expected to reclaim anything, if there is no autofs mount anymore?

When the Node plugin Pod is being deleted, kubelet sends SIGTERM to the containers’ main process. As expected, this indeed triggers automount’s mount clean up. This inadvertly breaks the autofs bindmounts in all consumer Pods and what’s worse, there is no way for the consumers to restore access and they all would need to be restarted. There is a way to skip the mount clean up though: instead of the SIGTERM signal, the automount’s container sends SIGKILL to the daemon when shutting down. With this “trick” the autofs mount is kept, and we are able to make the daemon reconnect and serve requests again. Additionally, a small but important detail is that the reconnect itself involves communication with the autofs kernel module via /dev/autofs device, and so it needs to be made available to the Node plugin Pod.

Related to that, the /cvmfs autofs root must be exposed via a hostPath, and be a shared mount (i.e. mount --make-shared, or mountPropagation: Bidirectional inside the Node plugin Pod manifest). Reclaiming the autofs root wouldn’t be possible if the mountpoint was tied to the Node plugin Pod’s lifetime, and so we need to persist it on the host. One thing to look out for is that if there is something periodically scanning mounts on the host (e.g. node-problem-detector, some Prometheus node metrics scrapers, …), it may keep reseting autofs’s mount expiry. In these situations it’s a good idea to exempt the autofs mountpoints from being touched by these components.

Okay, we have the root mountpoint covered, but what about the inner mounts inside /cvmfs? Normally we wouldn’t need to worry about them, but the CVMFS client is FUSE-based filesystem driver, and so it runs in user-space as a regular process. Deleting the Node plugin Pod then shuts down not only the automount daemon, but all the FUSE processes backing the respective CVMFS mounts. This causes a couple of problems:

- (a) losing those FUSE processes will cause I/O errors,

- (b) since we SIGKILL’d automount, the mounts still appear in the mount table and are not cleaned up,

- (c) automount doesn’t recognize the errors reported by severed FUSE mounts (

ENOTCONNerror code) and this prevents mount expiry from taking place.

While we cannot do anything about (a), (c) is the most serious in terms of affecting the consumers: if expiration worked, the severed mounts would be automatically taken down, and eventually mounted again (the next time the path is accessed), effectively restoring them. To work around this, we deploy yet another container in the Node plugin Pod. Its only job is to periodically scan /cvmfs for severed FUSE mounts, and in case it finds any, it unmounts them. To remount it, all it takes is for any consumer Pod on the node to access the respective path, and autofs will take care of the rest.

Conclusion

autofs is not very common in CSI drivers, and so there is not a lot of resources online on this subject. We hope this blogpost sheds a bit more light on the “how” as well as the “why”, and shows that as long as things are set up correctly, automounts indeed work fine in containers. While we have encountered numerous issues, we’ve managed to work around most of them. Also, we are in contact with the upstream autofs community and will be working towards fixing them, improving support for automounts in containers.

Summary check-list:

- Node plugin needs to be run with

hostPID: true - autofs root must be a shared mount in a hostPath

- bindmounting autofs should be done with

mount --rbind --make-slave - unmounting autofs bindmounts should be done with

umount --recursive - Node plugin Pods need access to

/dev/autofs - the automount daemon should be sent SIGKILL when shutting down

Resources:

GitLab Runners and Kubernetes: A Powerful Duo for CI/CD

Introduction

A GitLab runner is an application that works with GitLab CI/CD to run jobs in a pipeline. GitLab at CERN provides runners that are available to the whole instance and any CERN user can access them. In the past, we were providing a fixed amount of Docker runners executing in Openstack virtual machines following an in-house solution that utilized docker machine. This solution served its purpose for several years, but docker machine was deprecated by Docker some years ago, and a fork is only maintained by GitLab. The last few years CERN’s GitLab licensed users have increased and together with them, even more the number of running pipelines, as Continuous Integration and Delivery (CI/CD) is rapidly adopted by everyone. We needed to provide a scalable infrastructure that would facilitate our users’ demand and CERN’s growth and Kubernetes Runners seemed promising.

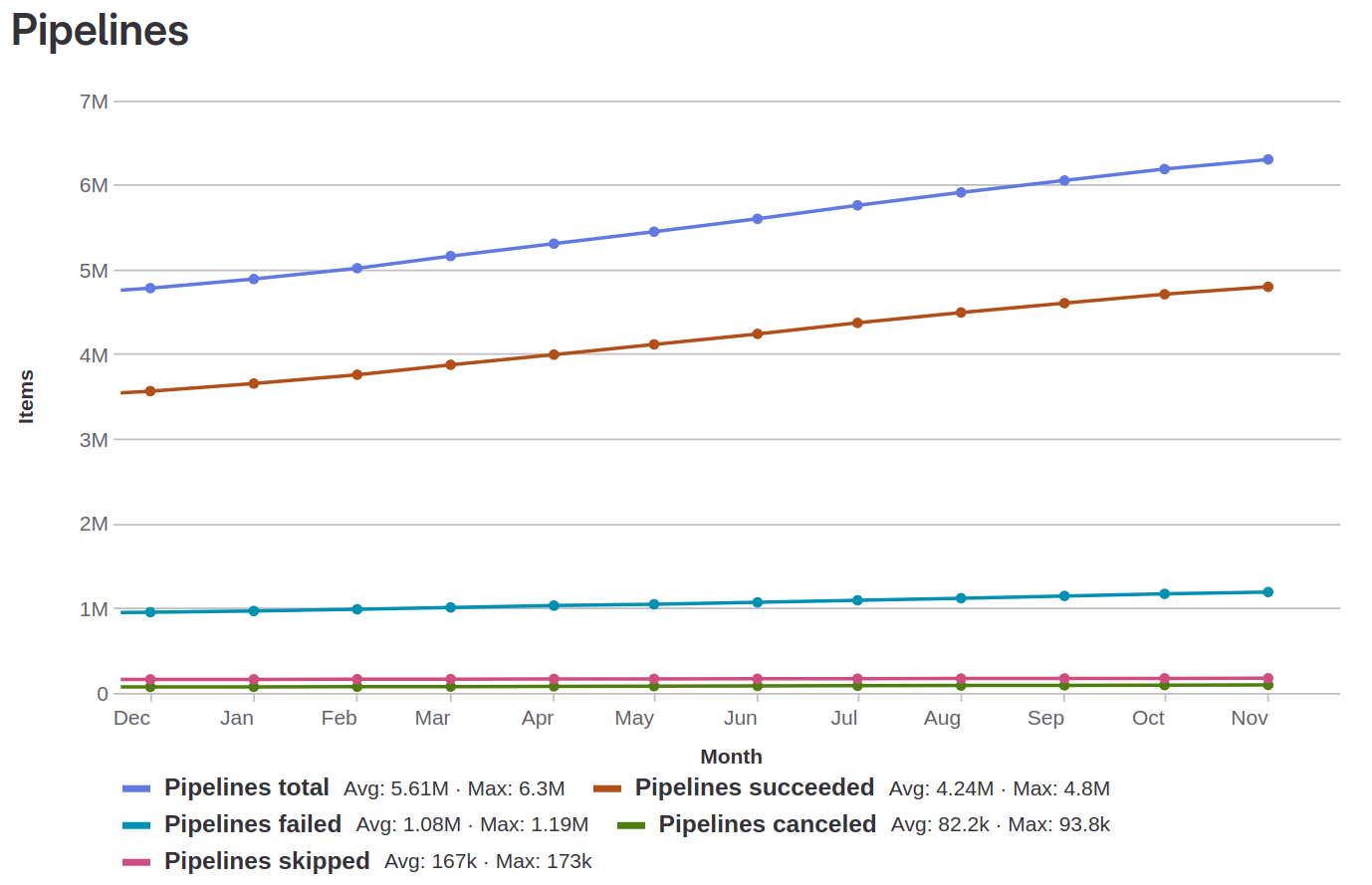

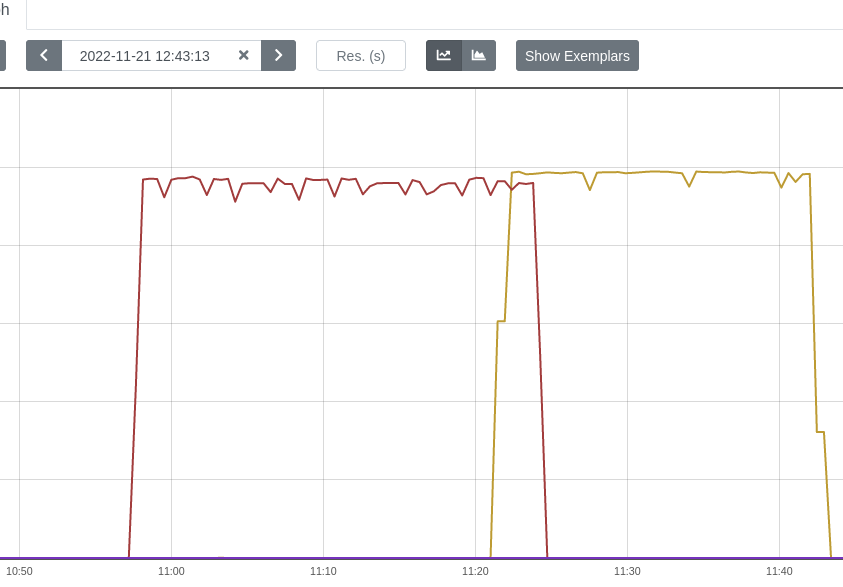

Figure 1: Evolution in the Number of Pipelines over the last year (Dec 2022 – Nov 2023)

Kubernetes+executor Runners: Our new powerful tool

The Kubernetes runners come with the advantages that Kubernetes have in terms of reliability, scalability and availability providing a robust infrastructure for runners to flourish hand by hand with our users’ activities. The new infrastructure has many advantages over the old one. It is safe to say that it suits our needs better as a big organization with a range of activities in research, IT infrastructure and development. Some of the advantages that Kubernetes Runners have are:

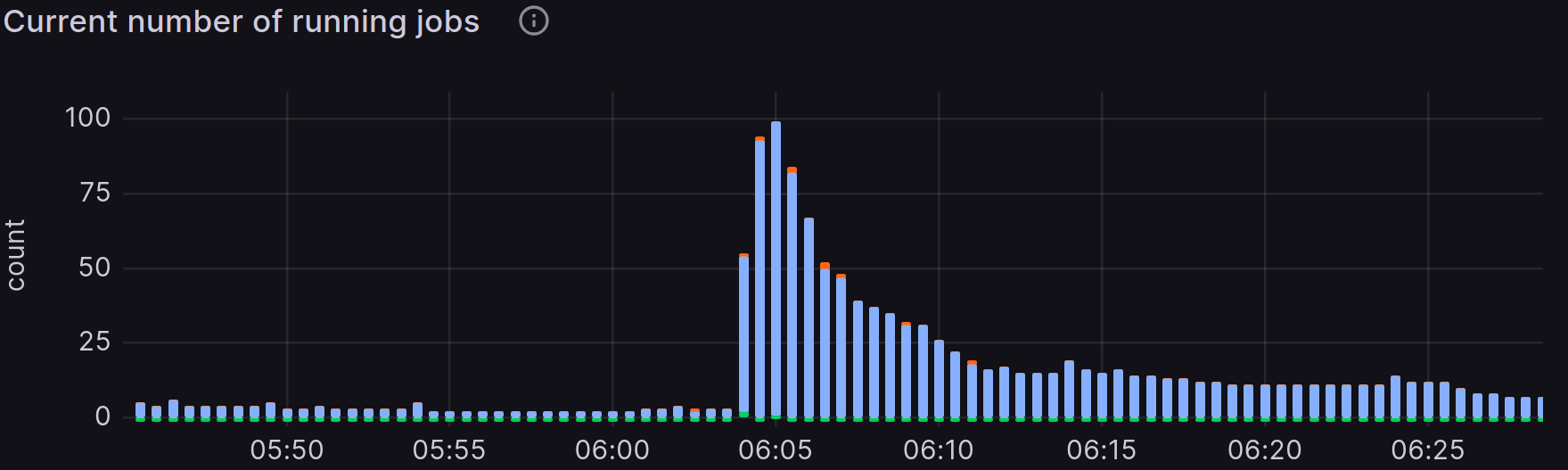

- Scalability: Kubernetes runners can scale from 0 to 100 pods at any given time depending on the demand across more than 20 nodes. We can also scale the cluster to any number of nodes to execute 200 jobs concurrently seamlessly, if the demand increases in the future. Here is a time frame in which instance runners went from 0 to 100 jobs in a minute.

Figure 2: Grafana table of the running jobs in relation to time

Having multiple clusters gives us this advantage multiple times since the jobs are distributed in different specialized clusters depending on the users’ needs.

-

Multi Cluster Support: With multiple clusters, we are able to provide a variety of capabilities to our users based on their needs. Having 19,000 users, physicists, machine learning developers, hardware designers, software engineers means that there is not a silver bullet for shared runners. Hence, it is GitLab’s great responsibility to provide multiple instances to facilitate users’ activities. Those instances are:

- Default cluster: Generic runners that can accommodate the vast majority of jobs.

- CVMFS cluster: CVMFS stands for CernVM File System. It is a scalable, reliable, and low-maintenance software distribution service. It was developed to assist High Energy Physics (HEP) collaborations to deploy software on the worldwide-distributed computing infrastructure used to run data processing applications. The CVMFS Cluster mounts CVMFS volumes per job.

- ARM cluster: For building ARM executables with the advantages that this architecture has such as high performance, energy efficiency, and integrated security.

- FPGA cluster: At CERN, FPGAs are extensively used not only in scientific experiments but also in the operation of accelerators, where they provide specialized circuits tailored for unique applications. To support the development of these FPGA-based systems, CERN’s CI/CD infrastructure includes customized runners designed to handle FPGA development-related jobs.

- Apache Spark cluster: Apache Spark is a general-purpose distributed data processing engine and vastly used at CERN for several data analytics applications regarding research for high energy physics, AI and more.

We also have plans to incorporate new clusters in our toolbox. Those are:

- GPU cluster: Specialized runners to run jobs on GPUs for highly parallelizable workloads to accelerate our applications regarding machine learning and data processing

- Technical Network cluster: An air-gapped deployment offering connectivity for accelerator control devices and accelerator related industrial systems at CERN.

-

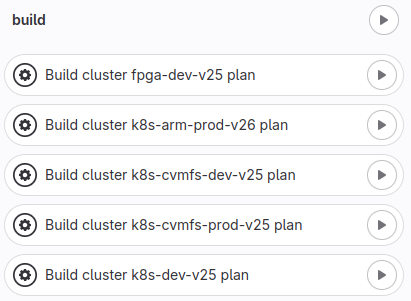

Easy Cluster Creation: We used Terraform to create clusters seamlessly for the different types of clusters we use as mentioned earlier. To achieve this, we used the GitLab Integration with Terraform and we are also following up OpenTofu. Furthermore, in case of a severe issue or a compromise of a cluster, we can bring the cluster down and create a new one with very few manual steps. Here is a part of our pipeline that we use to create clusters.

Figure 3: Part of the cluster creation pipeline

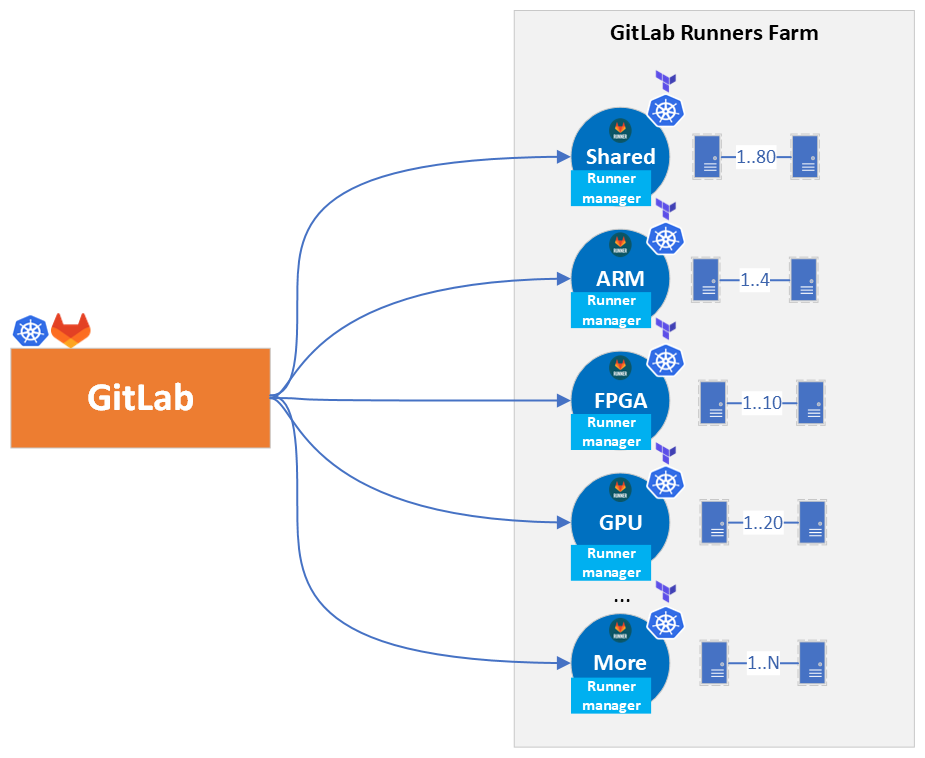

Architectural Overview

Let’s take a step back and see the big picture, what decisions we made and why. The following Figure 4 represents the architecture overview of the installation we implemented. The deployment of the runners has been decoupled from the GitLab cluster which has a lot of benefits:

- Cluster decoupling: Previously, the Docker executors were deployed in the same cluster as the GitLab application. Now, the runners have their own clusters which gives the advantage to maintain them separately, organize the infrastructure and runners’ configuration better per environment, and have specific end-to-end tests which allows us to verify their operability without interfering with the GitLab Application.

- Zero downtime Cluster upgrades: With this architecture we can upgrade the runners’ clusters to a more recent Kubernetes version with zero downtime by simply creating a new cluster and then registering it as an instance runner with the same tags, and finally decommissioning the old cluster. When both clusters are simultaneously running, GitLab will balance the jobs between them.

- Scaling-up: GitLab Service has a QA infrastructure to verify and assure the quality of the service before releasing. As such, this instance comes with its own set of runners which can be registered to the production instance at any time, scaling the GitLab infrastructure up to the required demand in an emergency situation.

Figure 4: GitLab connection to Runners Architecture Overview

How we migrated to K8s Runners?

In order to migrate to the GitLab runners we performed a series of steps detailed next:

- Creation of a temporary tag (k8s-default)

- Opt-in offering and randomly selection of users to try them out

- Accept untagged jobs

- Finally, decommission Docker runners

Lets see the above in more detail.

![Figure 5: GitLab runners migration tImeline [2023]](/blog/2023/12/06/gitlab-runners-and-kubernetes-a-powerful-duo-for-ci/cd/images/migration-timeline.png)

Figure 5: GitLab runners migration tImeline [2023]

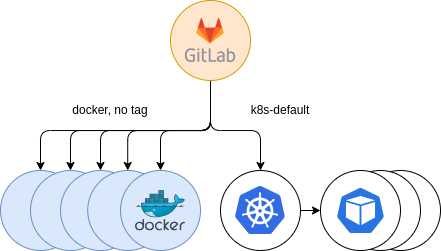

After setting up the clusters and registering them in GitLab, we announced a temporary tag for users interested in using the new runners, named k8s-default. Jobs were running in the new executor successfully without any problems and more and more users opted-in to try our new offering. This certainly helped us troubleshooting GitLab Runners, and start getting acquainted and embracing a very valuable experience and know-how on them.

Figure 6: Initial Kubernetes providing. Opt-in

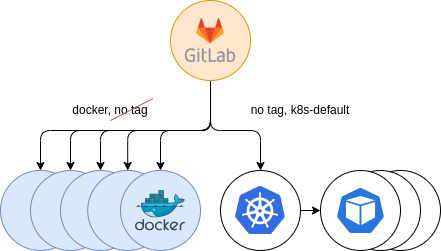

The next step was to gradually accept jobs from untagged jobs. We kept supporting previous Docker runners, in order to provide a fallback mechanism for users that, in the event of starting to use the new Kubernetes runners, experienced some errors. Thus, users using the docker tag in their .gitlab-ci.yml configuration file, would automatically land in the Docker runners, while those with untagged jobs, in addition to the k8s-default tag, started landing in the new Kubernetes runners. This gave us some insights of problems that could occur and to solve them before the full migration.

Figure 7: Secondary Kubernetes providing. Parallel to Docker

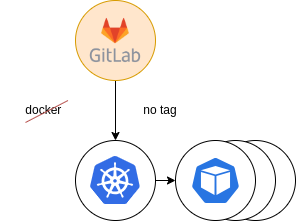

The last step was to decommission the old runner tags and move everything to the new infrastructure.

Figure 8: Final providing. Docker decommission

As a result, the Kubernetes runner accepted all the load and users that didn’t migrate to the new runners already had been forced to do it.

Errors and pitfalls

Such a big migration to the new runners had some problems and pitfalls that we discovered as we went through. Several analysis, investigations and communication with users helped us address them, aiming at providing a stable environment for our community. Here are some of the tricky problems we solved:

- Ping: Ping was disabled by default and some jobs were failing. This is caused by the security hardening Kubernetes has which disables all sysctls that may be used to access kernel capabilities of the node and interfere with other pods, including the NET_RAW capability which includes all network sysctls for the pod.

- CVMFS: There was a missing configuration in the Kubernetes configmap that was setting up the mount to the CVMFS file system, but thanks to our colleagues from the Kubernetes Team this has been solved in recent versions of CERN Kubernetes clusters (>=1.26). New clusters will benefit from this improvement.

- IPV6: The new runners are mainly using IPV6 addresses and some users that used IPV4 experienced problems in test cases that run lightweight web servers in, for example, address 127.0.0.1. This is because the pods run their own private network while the Docker runners used the host’s one.

- Entrypoint: The entrypoint in a Docker image is not executed by default due to the recent feature flag introduced in the new GitLab runners based on Kubernetes about honoring (or not) the entrypoint (FF_KUBERNETES_HONOR_ENTRYPOINT). This was not the case for Docker runners, where all runners were executing the entrypoint script in the beginning of the job. It led users into a situation where they hit a limitation, when after honoring the entrypoint of a Dockerfile, this entrypoint contained environment variables defined in the GitLab CI/CD variables. This approach is not valid anymore, and GitLab recommends using/moving the content of this entrypoint to the before_script keyword whenever possible.

- Ulimit Issue: The new Kubernetes cluster we created sets the limit of the file descriptors (ulimit) of the pods that it spawns to the maximum number possible. This is due to a default configuration in the container runtime (in our case, containerd), that in recent versions of Kubernetes, set its limit to

Infinity, the highest possible value. This caused some pods to run really slow and users complained that their jobs, which previously ran in minutes, now hang and after an hour the job was killed. This issue was challenging to address, but it was mainly related to images based on CentOS7, thus needing a lower limit to operate properly, as per this kernel bug. Nevertheless, thanks to the “pre_build_script” setting available in the GitLab Runners configuration, we could “inject” an appropriate ulimit value for all jobs, working around the issue.

Furthermore, we ran into many GitLab bugs that we raised with GitLab’s developers to be assessed, such as an issue that does not allow users to see environment variables in the Terminal or missing documentation that is crucial for customers.

As a result, CERN is becoming a more prominent figure and valued collaborator in the GitLab community through all our contributions and presence.

Security

When we transitioned from Docker runners to Kubernetes runners, it brought a significant improvement in security through the implementation of the UserNamespacesStatelessPodsSupport feature. This feature offered a substantial enhancement to the security of containerized workloads compared to the older Docker setup.

With UserNamespacesStatelessPodsSupport in Kubernetes, we were able to establish a clear separation between containerized applications and the underlying host system by running pods and containers with different user and group IDs than the host system, and by mapping them to different user namespaces. This was a security measure as it mitigated, among others, the risks associated with running containers as the root user on the host system, which could be exploited by malicious actors, potentially leading to the entire system being compromised. The implementation of UserNamespacesStatelessPodsSupport enabled users to effectively isolate containers and their workloads from the host system, thereby enhancing overall system security.

We are committed to the continuous enhancement of our security measures, with a proactive approach to implementing additional safeguards as soon as they become available. For example, it is planned to disable umask 0000 for the Kubernetes runners pods, adopting and going a step further with the security measures and best practices that have been already implemented in docker machine executor runners.

Future Security Hardening

We are actively collaborating with the CERN Security Team to establish comprehensive Security Policies for projects. These security policies are designed to enforce best practices and keep workflows up-to-date. Our collaboration with the CERN Security Team aims to establish a framework that ensures user compliance and promotes a security-conscious culture in our environment. We will talk more about security policies on a separate topic in the near future.

Conclusion and Future plans

Ultimately, with the GitLab Kubernetes runners, we managed to vastly improve the number of concurrent jobs being executed, support different workflows and cut the operational cost of the infrastructure. As we mentioned above, decoupling the clusters speeds up vastly the way we deploy, test and provide the runners, gaining in maintainability aspects.

Our future plans include the provisioning of privileged Kubernetes runners that will set the tombstone in the old docker machine runners and will complete the turnover for Kubernetes runners. It will be challenging, but we are determined to accomplish this following GitLab’s decisions and best practices.

All in all the Git Service is proud of providing our users with an exceptional infrastructure that facilitates the needs of the huge CERN scientific community. We would like to wholeheartedly thank the users that supported us with this improvement and helped us to find out breaking points of the new Kubernetes runners. Together, we managed to stabilize the new runners to be a powerful item in our tool case.

Happy GitLabing to all!

The GitLab Team

Ismael Posada Trobo ismael.posada.trobo@cern.ch

Konstantinos Evangelou konstantinos.evangelou@cern.ch

Subhashis Suara subhashis.suara@cern.ch

Special Thanks to

Ricardo Rocha for his suggestions and support

Nurturing Sustainability: Raising Power Consumption Awareness

Supervisors: Diana Gaponcic, Ricardo Rocha

With modern society relying more and more on digital services this has led to an explosive growth in data centres and cloud-based applications. This growth comes at a cost – data centres are power-hungry and contribute significantly to carbon emissions. To address this, multiple efforts and projects have been looking at integrating sustainability practices in all tech areas, including containers and clusters.

As part of my summer internship with CERN openlab i had the chance to join the CERN Kubernetes team to try out some of these tools, and hopefully launch the first steps to integrate them with the CERN infrastructure.

While having fun, travelling, and making new friends at the same time…

This blog post focuses on finding ways to populate power consumption metrics and visualize them in meaningful ways. It should help raise awareness and find ways to minimize the carbon footprint without compromising application efficiency.

In this blog post, we use Kepler to estimate the power consumption. While this project is obviously a good choice due to its active open-source community, multiple installation ways, and various well-documented metrics, there are some other promising projects in the ecosystem worth trying out.

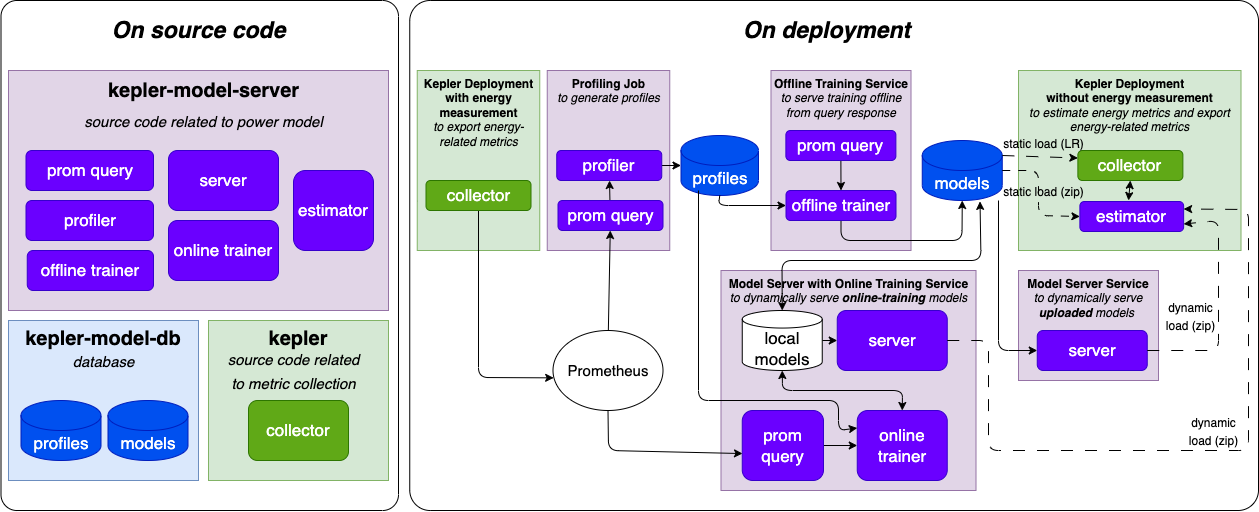

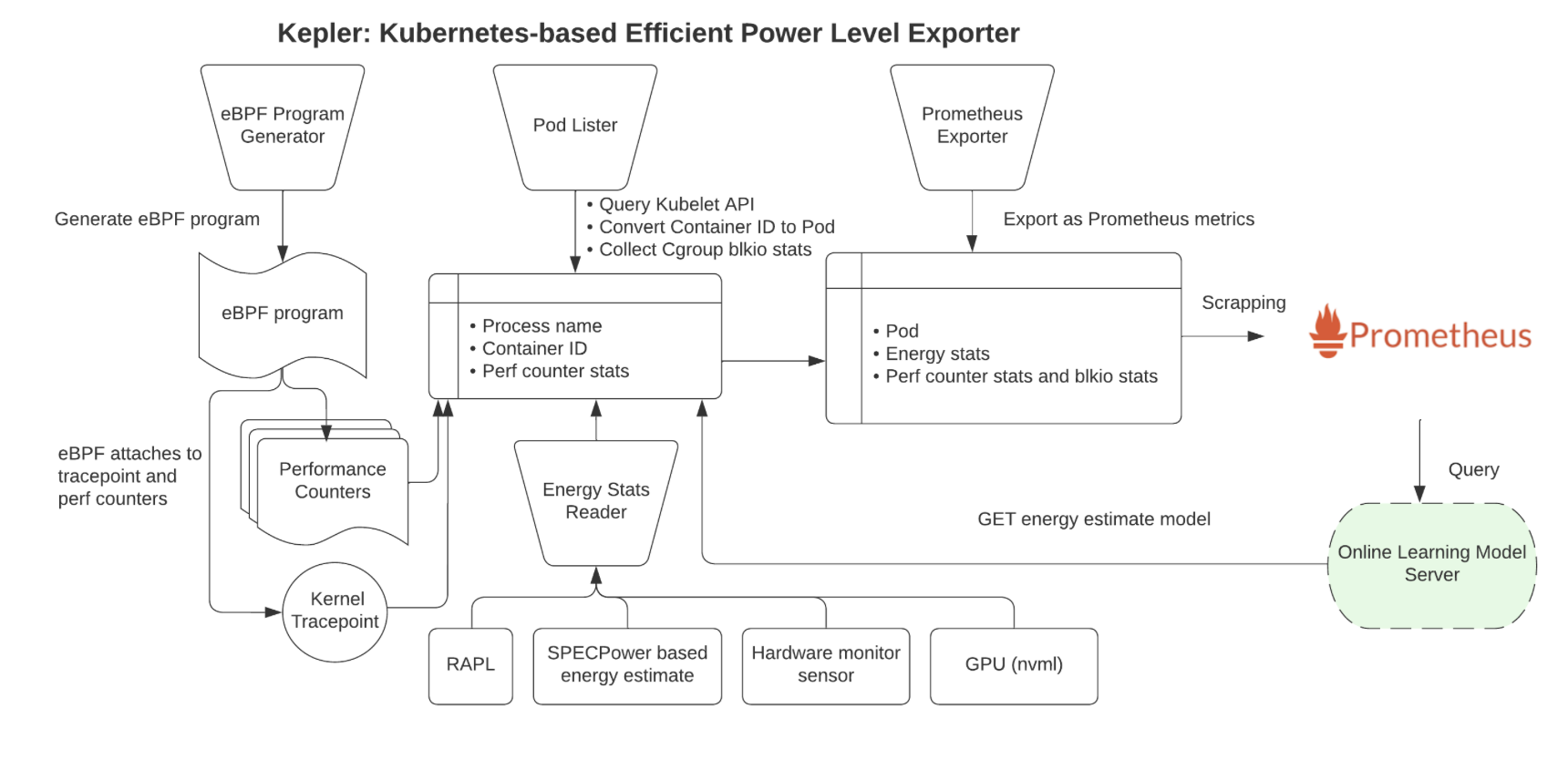

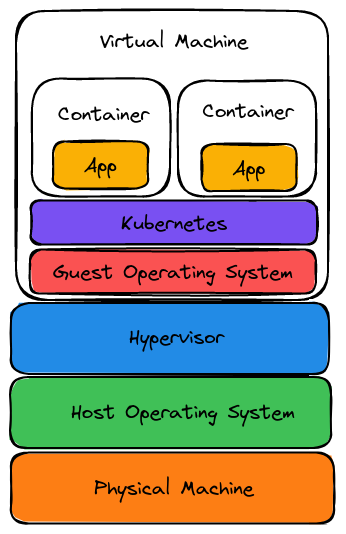

Kepler Architecture

Kepler (Kubernetes Efficient Power Level Exporter) is an open-source project that uses eBPF to probe CPU performance counters and Linux kernel tracepoints. This data can then be put against actual energy consumption readings or fed to a machine learning model to estimate energy consumption, especially when working with VMs where this information is not available from the hypervisor. The metrics are exported to Prometheus and can be integrated as part of the monitoring. An overview of the architecture can be seen below:

Source: github.com/sustainable-computing-io/kepler-model-server

Kepler Exporter

The Kepler Exporter is a crucial component responsible for exposing the metrics related to energy consumption from different Kubernetes components like Pods and Nodes.

Source: github.com/sustainable-computing-io/kepler

- The Kepler Exporter collects energy consumption metrics from Kubernetes components such as Pods and Nodes using eBPF.

- The metrics are available in Prometheus and be be visualized with Grafana.

- Later, the metrics could be utilized to make scheduling decisions to optimeze the power consumption.

To find more about eBPF in Kepler consult the documentation.

Kepler Model Server

The Kepler Model Server plays a central role in the Kepler architecture. It is designed to provide power estimation models based on various parameters and requests. These models estimate power consumption based on factors like target granularity, available input metrics, and model filters.

- The Kepler Model Server receives requests from clients, which include details about the target granularity (e.g., node, pod), available input metrics, and model filters.

- Based on these requests, the server selects an appropriate power estimation model.

- The Kepler Estimator, which is a client module, interacts with the Kepler Model Server as a sidecar of the Kepler Exporter’s main container. It serves PowerRequests by utilizing the model package defined in Kepler Exporter’s estimator.go file via a unix domain socket.

There is also the possibility of deploying an online-trainer. It runs as a sidecar to the main server, and executes training pipelines to update the power estimation model in real-time when new power metrics become available.

Kepler Estimator

The Kepler Estimator serves as a client module to the Kepler Model Server, running as a sidecar of the Kepler Exporter’s main container. It handles PowerRequests and interacts with the power estimation models to provide power consumption estimates.

- The Kepler Estimator acts as a client module to the Kepler Model Server.

- It receives PowerRequests from the model package in the Kepler Exporter via a unix domain socket (/tmp/estimator.sock).

- The Kepler Estimator uses the power estimation models available in the Kepler Model Server to calculate power consumption estimates based on the provided parameters.

- These estimates are then available to the Kepler Exporter.

Installation

The project was designed to be easily installed, and provides multiple ways to do so:

- using an existing helm chart

- building manifests with make

- using the Kepler operator

We tried all installation options. While all methods should work out of the box, we encountered a few issues and settled on building the manifests using make. The command used is:

make build-manifest OPTS="PROMETHEUS_DEPLOY ESTIMATOR_SIDECAR_DEPLOY MODEL_SERVER_DEPLOY"

More configuration options can be found in the documentation.

Running the command above and applying the resulting manifests deploys an exporter (with the estimator as a sidecar) on each node, and the model server:

$ kubectl get pod -n kepler

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kepler-exporter-8t6tb 2/2 Running 0 18h

kepler-exporter-bsmmj 2/2 Running 0 18h

kepler-exporter-k4dtb 2/2 Running 0 18h

kepler-model-server-68df498948-zfblr 1/1 Running 0 19h

Kepler projects provides a Grafana dashboard to visualize the metrics.

While the pods were running successfully, no data was available in Prometheus. This lead to some further investigations.

Issue 1: different number of headers and values in the request

The Kepler Estimator module receives a request from the exporter similar to:

"cpu_time","irq_net_tx","irq_net_rx","irq_block","cgroupfs_memory_usage_bytes",

"cgroupfs_kernel_memory_usage_bytes","cgroupfs_tcp_memory_usage_bytes","cgroupfs_cpu_usage_us",

"cgroupfs_system_cpu_usage_us","cgroupfs_user_cpu_usage_us","cgroupfs_ioread_bytes",

"cgroupfs_iowrite_bytes","block_devices_used","container_cpu_usage_seconds_total",

"container_memory_working_set_bytes","block_devices_used"],"values":[[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0]],"output_type":"DynComponentPower","system_features":["cpu_architecture"],

"system_values":["Broadwell"],"model_name":"","filter":""}

The request above will error with: {'powers': [], 'msg': 'fail to handle request: 16 columns passed, passed data had 15 columns'}.

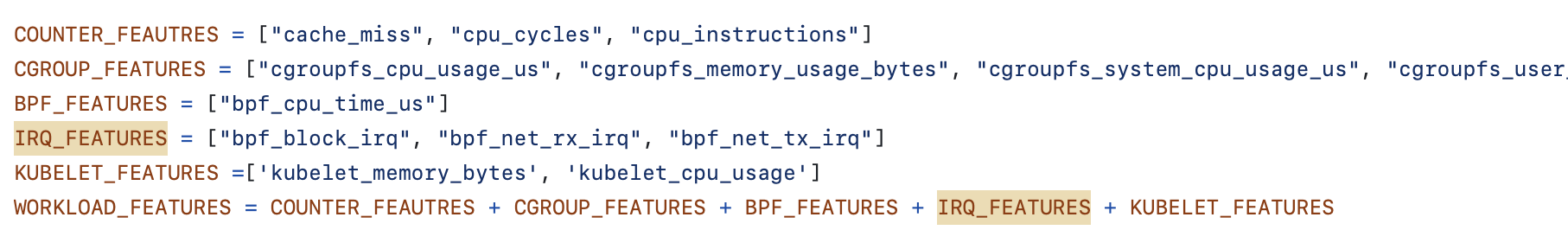

For some reason block_devices_used appears twice in the headers. After some investigation, we just added a check that examines the length of the header array and eliminates the last occurrence of “block_devices_used”. This issue needs further investigation.

Issue 2: IRQ metrics naming convention

In the Kepler Estimator request, the IRQ metrics have irq- at the beginning: irq_net_tx, irq_net_rx, and irq_block. At the same time, in the Kepler Model Server, -irq is placed at the end of the name.

Compare:

- In Kepler Estimator:

"cpu_time","irq_net_tx","irq_net_rx","irq_block","cgroupfs_memory_usage_bytes"... - In Kepler model server:

This missmatch prevents the model server from returning a model, because of the missing features:

valid feature groups: []

DynComponentPower

10.100.205.40 - - [18/Aug/2023 12:09:44] "POST /model HTTP/1.1" 400 -

To address the problem, an upstream issue was opened. The community was remarkably responsive, validating the problem and coming up with a fix.

Demo Time

Create some test load

After deploying Kepler and resolving the issues above, we can proceed and create some stress load using a tool called stress-ng. It is important to limit the memory the pod can utilize, to avoid other pods being killed.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: stress-ng

namespace: kepler

spec:

containers:

- name: stress-ng

image: polinux/stress-ng

command: ["sleep","inf"]

resources:

requests:

memory: "1.2G"

limits:

memory: "1.2G"

Some commands that were utilized in the analysis:

stress-ng --cpu 4 --io 2 --vm 1 --vm-bytes 1G --timeout 30sstress-ng --disk 2 --timeout 60s --metrics-briefstress-ng --cpu 10 --io 2 --vm 10 --vm-bytes 1G --timeout 10m --metrics-brief

For more available parameters consult the relevant documentation.

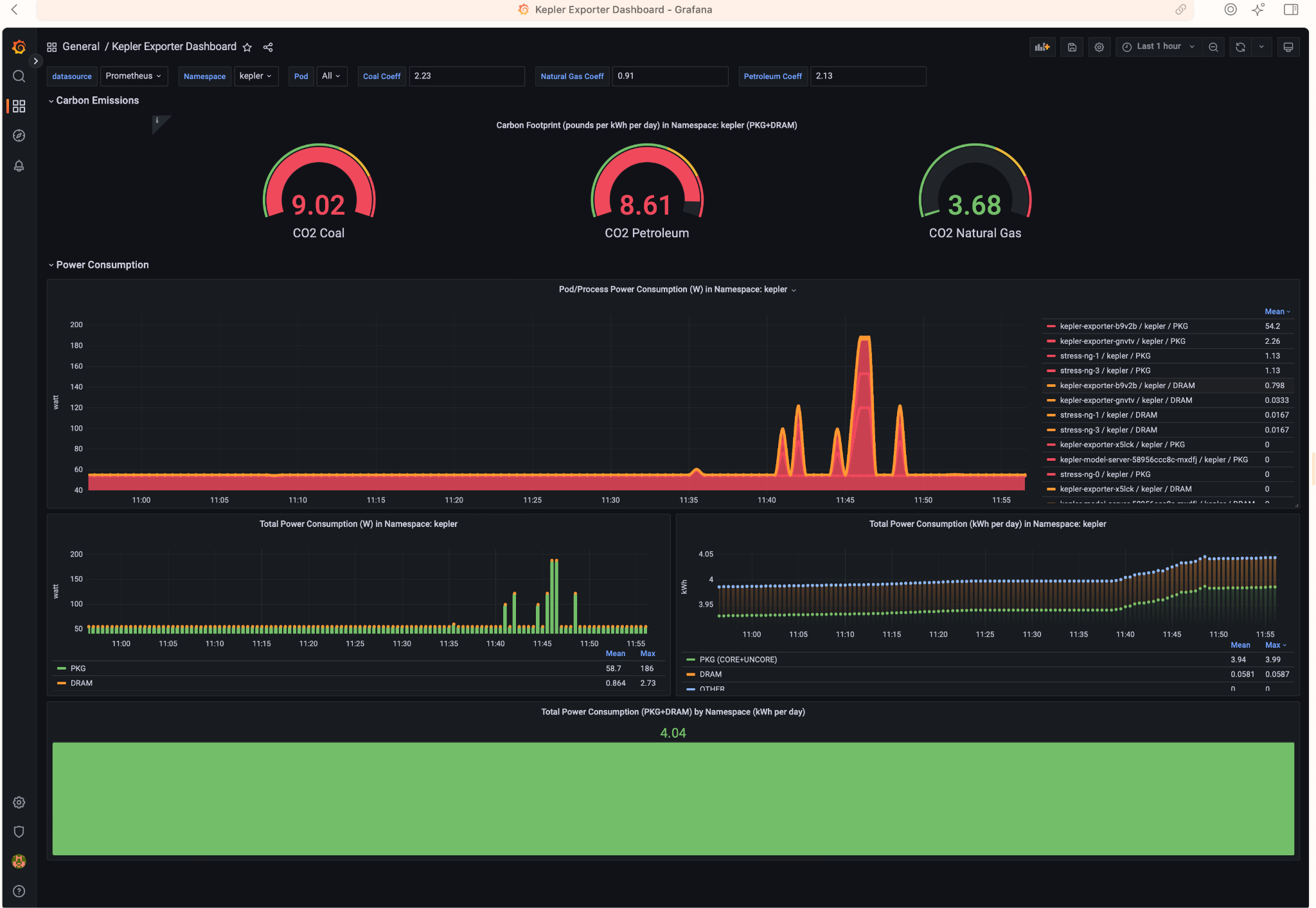

Analyzing the Results

Access Grafana Kepler dashboard and monitor the metrics when creating the test load. We can clearly see the spikes in power consumption:

We can monitor the power consumption per process/pod. For example If we choose only the stress-ng pod:

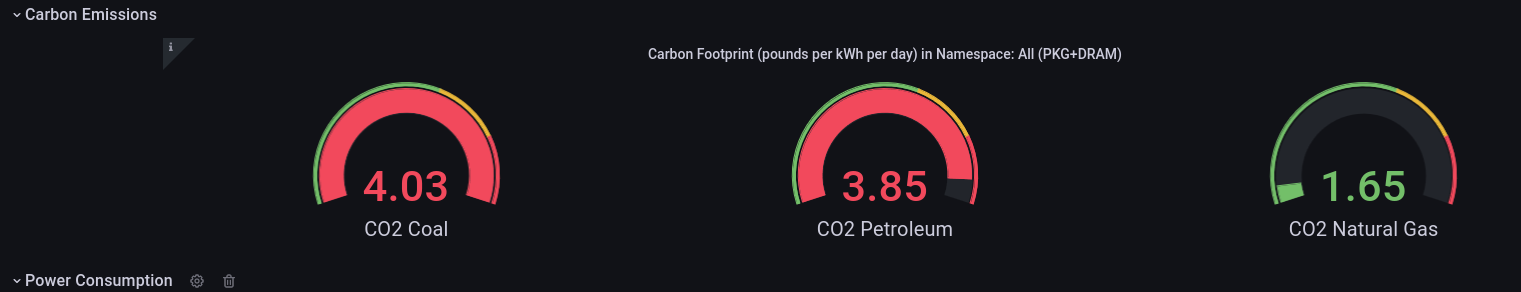

A panel worth to mention is “Carbon Footprint in Namespace”, where the metrics can be combined with power usage effectiveness (PUE) and electricity carbon intensity data to calculate the carbon footprint of the workload:

By observing resource utilisation and energy consumption at pod- and node- level we can better understand the environmental impact of a running Kubernetes cluster. Using data analysis we can make better decisions on how to allocate resources, optimize our workloads and architect our applications.

Conclusion and Future work

Engaging in a summer project focused on platform-aware scheduling using the Kepler library has proven to be a highly productive and valuable endeavor. This project has brought to light the substantial correlation between technology and environmental sustainability by exploring energy consumption metrics and carbon footprint data within Kubernetes clusters, both at the node and pod levels. Some future directions to take:

- To look into power aware scheduling:

While having fun, travelling, and making new friends at the same time…

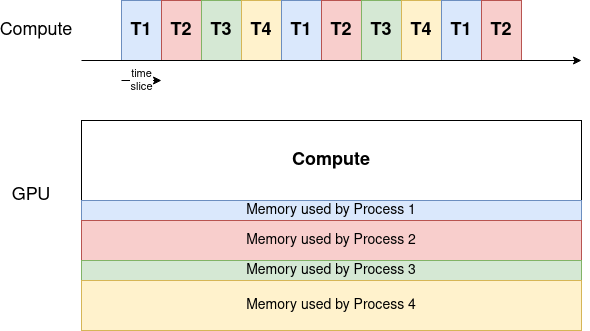

Efficient Access to Shared GPU Resources: Part 6

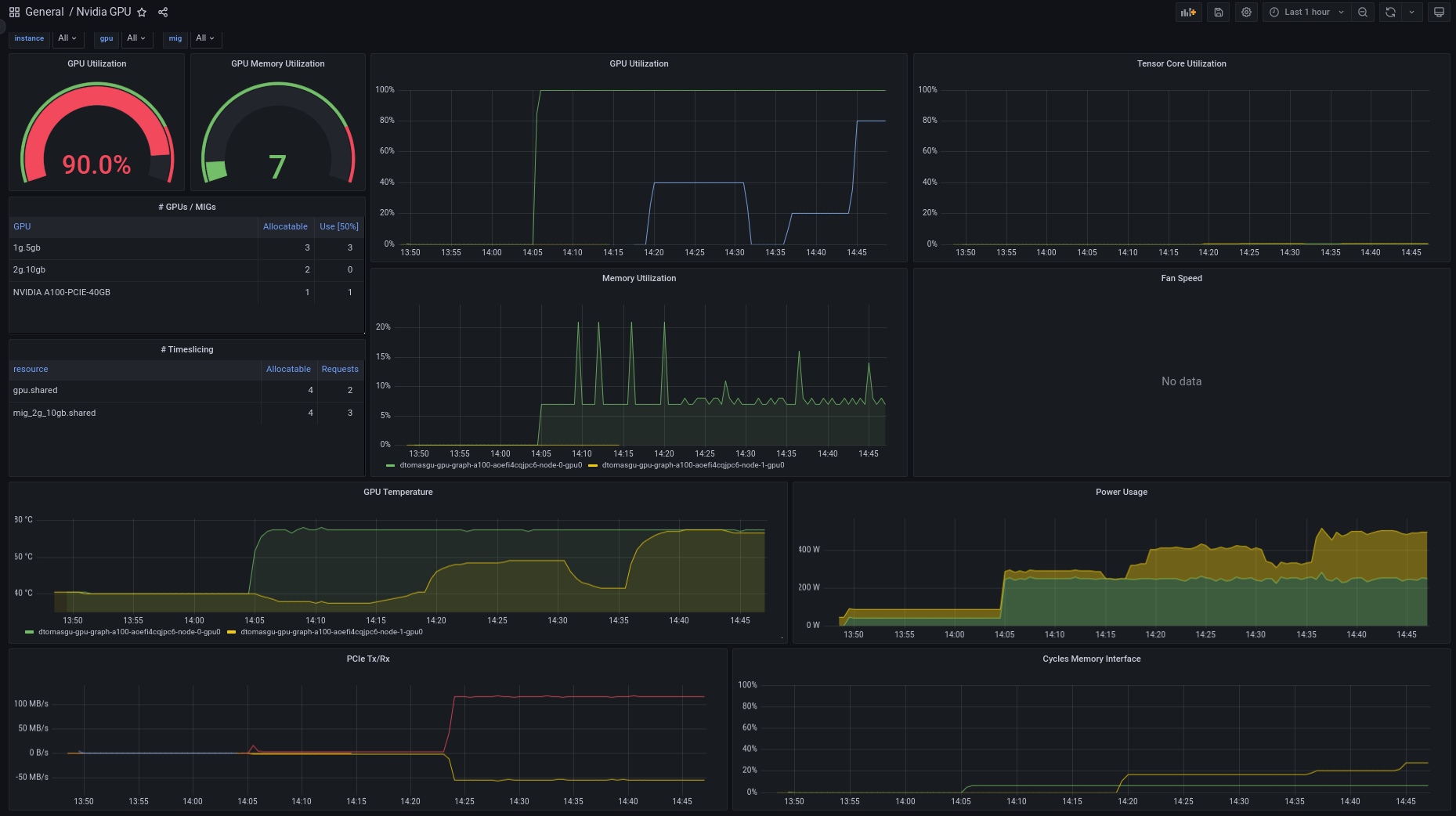

As the sixth blog post in our series, we are bringing a story about training a high energy physics (HEP) neural network using NVIDIA A100 GPUs using Kubeflow training operators. We will go over our methodology and analyze the impact of various factors on the performance.

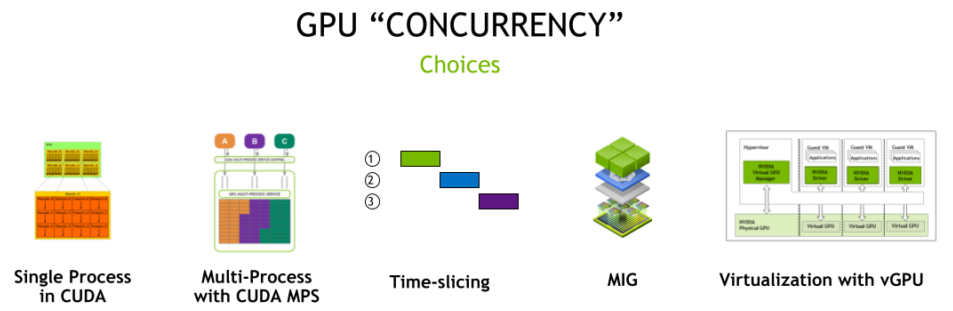

This series focuses on NVIDIA cards, although similar mechanisms might be offered by other vendors.

Motivation

Training large-scale deep learning models requires significant computational power. As models grow in size and complexity, efficient training using a single GPU is often not a possibility. To achieve efficient training benefiting from data parallelism or model paralellism, access to multiple GPUs is a prerequisite.

In this context, we will analyze the performance improvements and communication overhead when increasing the number of GPUs, and experiment with different topologies.

From another point of view, as discussed in the previous blog post, sometimes it is beneficial to enable GPU sharing. For example, to have a bigger GPU offering or ensure better GPU utilization. In this regard, we’ll experiment with various A100 MIG configuration options to see how they affect the distributed training performance.

We are aware that training on partitioned GPUs is an unusual setup for distributed training, and it makes more sense to give direct access to full GPUs. But given a setup where the cards are already partitioned to increase the GPU offering, we would like to explore how viable it is to use medium-sized MIGs instances for large training jobs.

Physics Workload - Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)

The computationally intensive HEP model chosen for this exercise is a GAN for producing hadronic showers in the calorimeter detectors. This neural network requires approximately 9GB of memory per worker and is an excellent demonstration of the benefits of distributed training. The model is implemented by Engin Eren, from DESY Institute. All work is available in this repository.

GANs have shown to enable fast simulation in HEP vs the traditional Monte Carlo methods - in some cases this can be several orders of magnitude. When GANs are used, the computational load is shifted from the inference to the training phase. Working efficiently with GANs necessitates the use of multiple GPUs and distributed training.

Setup

The setup for this training includes 10 nodes each having 4 A100 40GB PCIe GPUs, resulting in 40 available GPU cards.

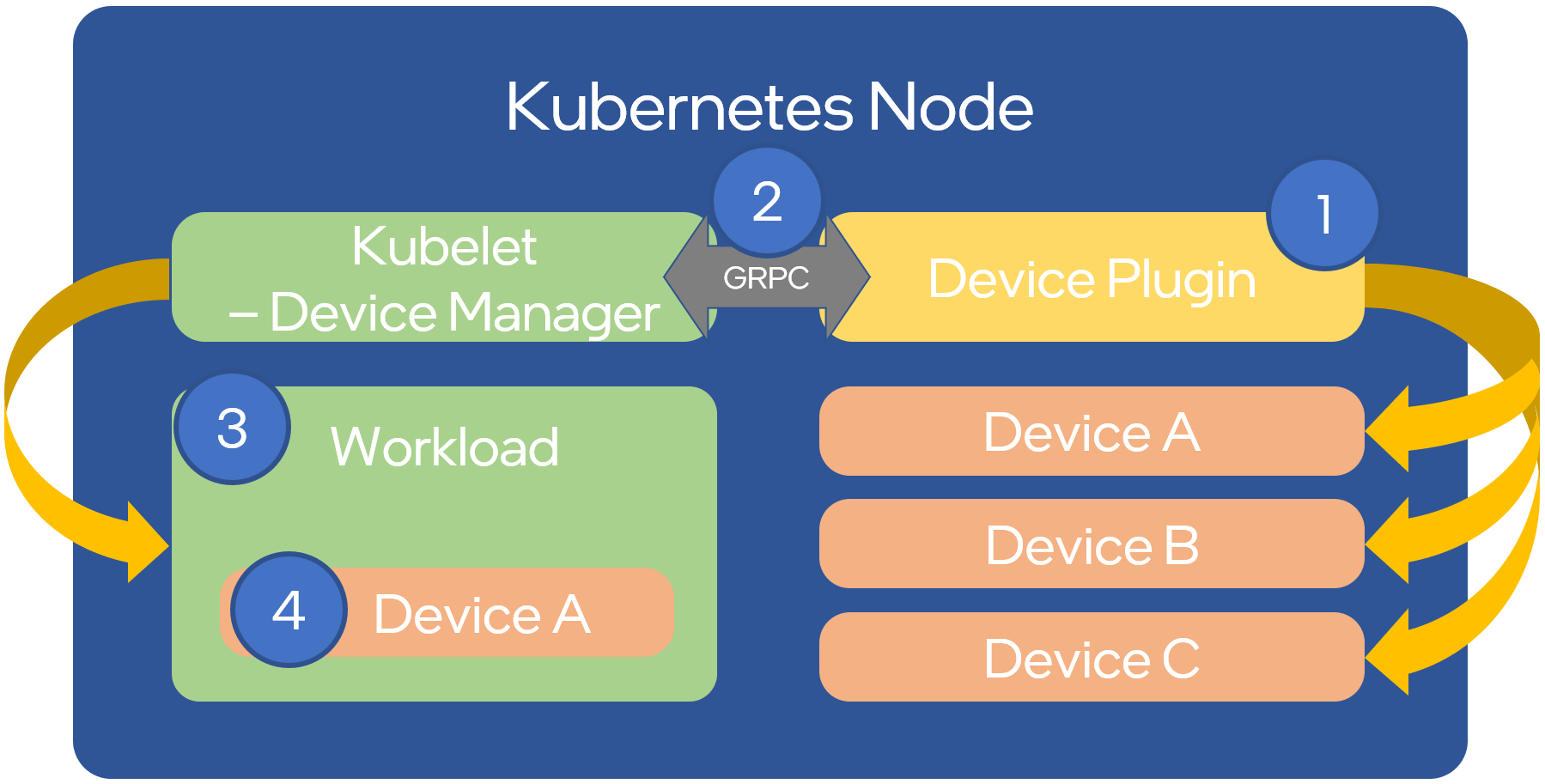

When it comes to using GPUs on Kubernetes clusters, the GPU operator is doing the heavy lifting - details on drivers setup, configuration, etc are in a previous blog post.

Training deep learning models using Kubeflow training operators requires developing the distributed training script, building the docker image, and writing the corresponding yaml files to run with the proper training parameters.

Developing a distributed training script

- TensorFlow and PyTorch offer support for distributed training.

- Scalability should be kept in mind when creating an initial modelling script. This means introducing distribution strategies and performing data loading in parallel. Starting the project in this manner will make things easier further down the road.

Building a Docker image with dependencies

- Consult the Dockerfile used for this analysis for more information.

- Kubeflow makes use of Kubernetes, a container orchestrator, which means that the distributed training will be run as a group of containers running in parallel and synchronizing with one another.

Creating a yaml file defining training parameters

- Training parameters include image name, the command to run, volume and network file system access, number of workers, number of GPUs in each worker, etc.

- Check the GAN PyTorchJob file used for more information.

The distributed training strategy used for training the GAN for producing hadronic showers in the calorimeter detectors is DistributedDataParallel from PyTorch, which provides data parallelism by synchronizing gradients across each model replica.

Training Time

Let’s start by training the model on 4, 8, 16, and 32 A100 40GB GPUs and compare the results.

| Number of GPUs | Batch Size | Time per Epoch [s] |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 64 | 210 |

| 8 | 64 | 160 |

| 16 | 64 | 120 |

| 32 | 64 | 78 |

Ideally, when doubling the number of GPUs, we would like to have double the performance. In reality the extra overhead smooths out the performance gain:

| T(4 GPUs) / T(8 GPUs) | T(8 GPUs) / T(16 GPUs) | T(16 GPUs) / T(32 GPUs) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.31 | 1.33 | 1.53 |

Conclusions:

- As expected, as we increase the number of GPUs the time per epoch decreases.

- As we double the number of GPUs, the 30% improvement achieved is lower than expected. This can be caused by multiple things, but one viable option to consider is using a different framework for distributed training. Examples include DeepSpeed or FSDP.

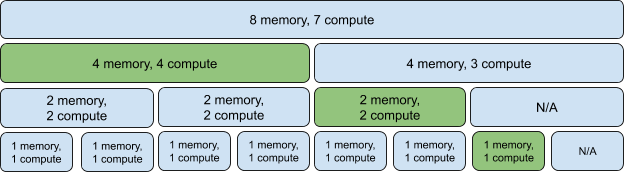

Bringing MIG into the mixture

Next, we can try and perform the same training on MIG-enabled GPUs. In the measurements that follow:

mig-2g.10gb- every GPU is partitioned into 3 instances of 2 compute units and 10 GB virtual memory each (3*2g.10gb).mig-3g.20gb- every GPU is partitioned into 2 instances of 3 compute units and 20 GB virtual memory each (2*3g.20gb).

For more information about MIG profiles check the previous blog post and the upstream NVIDIA documentation. Now we can redo the benchmarking, keeping in mind that:

- The mig-2g.10gb configuration has 3 workers per GPU, and mig-3g.20gb has 2 workers.

- On more powerful instances we can opt for bigger batch sizes to get the best performance.

- There should be no network overhead for MIG devices on the same GPUs.

2g.10gb MIG workers

| Number of A100 GPUs | Number of 2g.10gb MIG instances | Batch Size | Time per Epoch [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 12 | 32 | 505 |

| 8 | 24 | 32 | 286 |

| 16 | 48 | 32 | 250 |

| 32 | 96 | 32 | OOM |

The performance comparison when doubling the number of GPUs:

| T(12 MIG instances) / T(24 MIG instances) | T(24 MIG instances) / T(48 MIG instances) | T(48 MIG instances) / T(96 MIG instances) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.76 | 1.144 | OOM |

Conclusions:

- Huge improvements when scaling from 4 to 8 GPUs, the epoch time decreased from 505 to 286 seconds, about 76%.

- Doubling the number the GPUs again (from 8 to 16) improved the time by only ~14%.

- When fragmenting the training too much, we can encounter OOM errors.

- As we use DistributedDataParallel from PyTorch for data parallelism, the OOM is most likely caused by the extra memory needed to do gradient aggregation.

- It can also be caused by inefficiencies when performing the gradient aggregation, but nccl (the backend used) should be efficient enough. This is something to be investigated later.

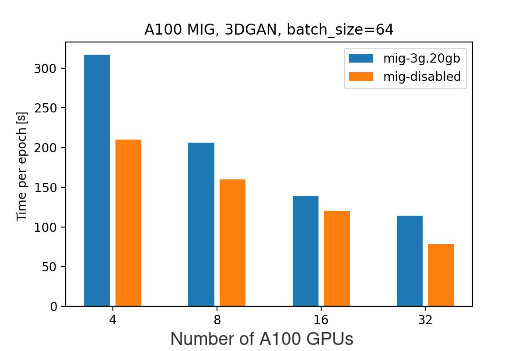

3g.20gb MIG workers

| Number of full A100 GPUs | Number of 3g.20gb MIG instances | Batch Size | Time per Epoch [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8 | 64 | 317 |

| 8 | 16 | 64 | 206 |

| 16 | 32 | 64 | 139 |

| 32 | 64 | 64 | 114 |

The performance comparison when doubling the number of GPUs:

| T(8 MIG instances) / T(16 MIG instances) | T(16 MIG instances) / T(32 MIG instances) | T(32 MIG instances) / T(64 MIG instances) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.53 | 1.48 | 1.21 |

Conclusions:

- When increasing the number of GPUs from 4 to 8, initially the scaling is less aggressive than it was for 2g.10gb instances (53% vs 76%), but it is more stable and allows to further increase the number of GPUs.

mig-3g.20gb vs mig-disabled:

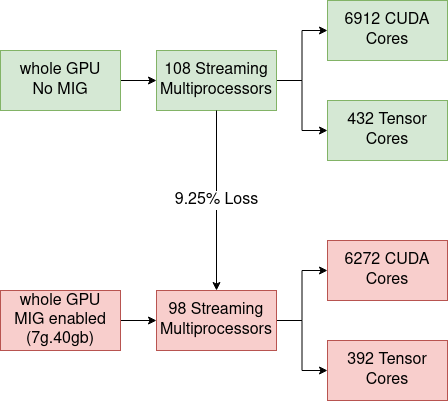

There are some initial assumptions we have, that should lead to the mig-disabled setup being more efficient than mig-3g.20gb. Consult the previous blogpost for more context:

- Double the number of Graphical Instances:

- In the mig-3g.20gb setup, every GPU is partitioned into 2, as a result, we have double the number of GPU instances.

- This results in more overhead.

- The number of SMs:

- For NVIDIA A100 40GB GPU, 1 SM means 64 CUDA Cores and 4 Tensor Cores

- A full A100 GPU has 108 SMs.

- 2 * 3g.20gb mig instances have in total 84 SMs (3g.20gb=42 SMs, consult the previous blog post for more information).

- mig-disabled setup has 22.22% more CUDA cores and Tensor Cores than mig-3g.20gb setup

- Memory:

- The full A100 GPU has 40GB of virtual memory

- 2 * 3g.20gb mig instances have 2 * 20 GB = 40 GB

- no loss of memory

Based on the experimental data, as expected, performing the training on full A100 GPUs shows better results than on mig-enabled ones. This can caused by multiple factors:

- Loss of SMs when enabling MIG

- Communication overhead

- Gradient synchronization

- Network congestion, etc.

At the same time, the trend seems to point out that as we increase the number of GPUs, the difference between mig-disabled vs mig-enabled setup alleviates.

Conclusions

- Although partitioning GPUs can be beneficial for providing bigger GPU offering and better utilization, it is still worth it to have dedicated GPUs for running demanding production jobs.

- Given a setup where GPUs are available but mig-partitioned, distributed training is a viable option:

- It comes with a penalty for the extra communication/bigger number of GPUs to provide same amount of resources.

- Adding small GPU instances can initially speed up the execution, but the improvement will decrease as more overhead is added, and in some cases the GPU will go OOM.

During these tests, we discovered that the training time per epoch varied significantly for the same input parameters (number of workers, batch size, MIG configuration). It led to the topology analysis that follows in the next section.

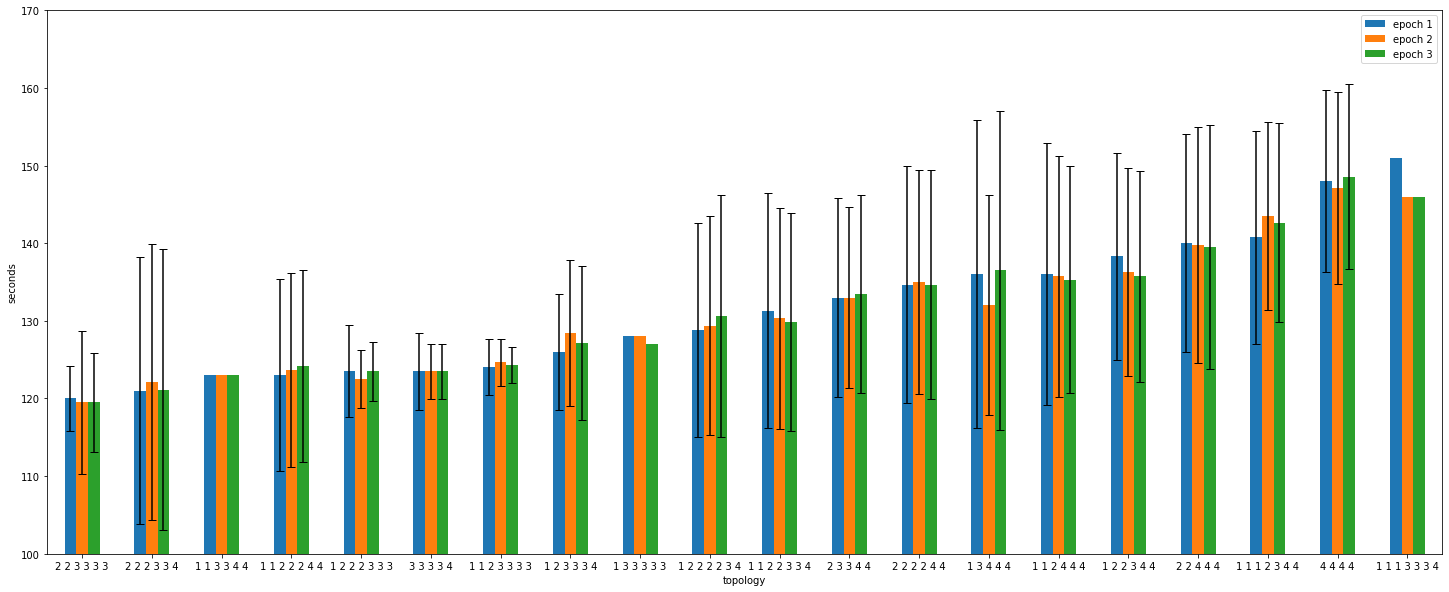

Topology

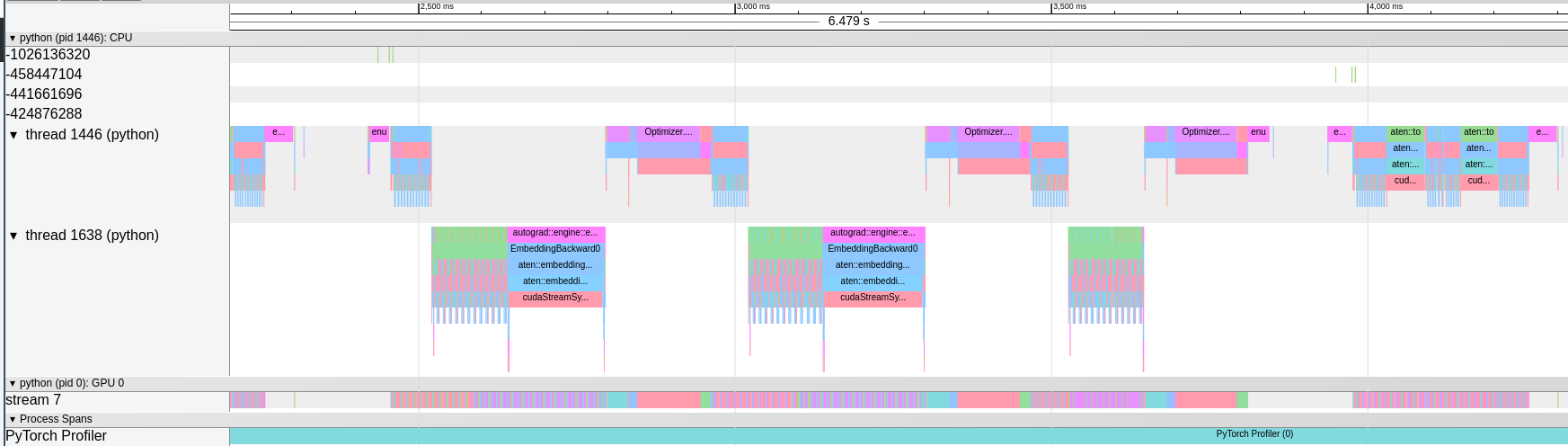

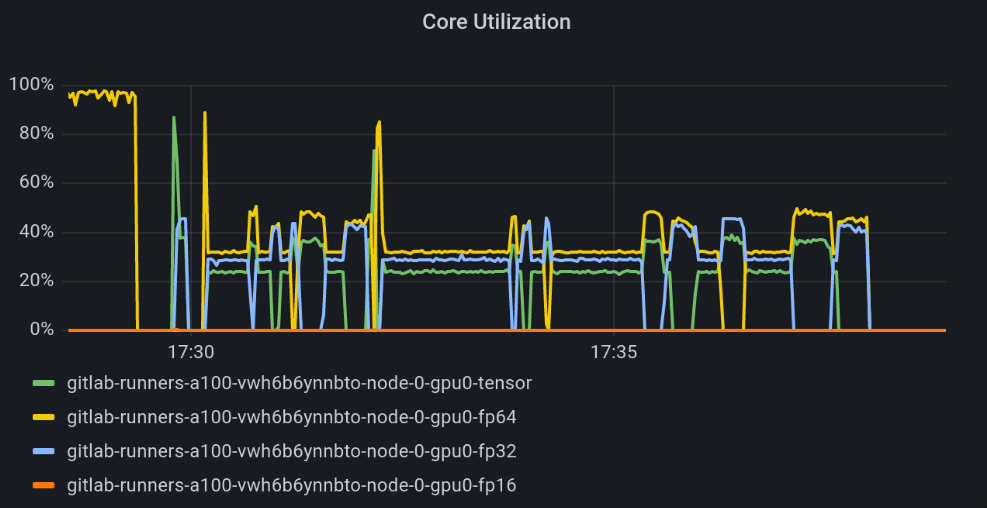

Getting variable execution times for fixed inputs lead to some additional investigations. The question is: “Does the topology affect the performance in a visible way?”.

In the following analysis, we have 8 nodes, each having 4 A100 GPUs. Given that we need 16 GPUs for model training, would it be better and more consistent if the workers utilized all 4 GPUs on 4 machines, or if the workers were distributed across more nodes?

To represent topologies, we will use a sequence of numbers, showing how many GPUs were in-use on different nodes.

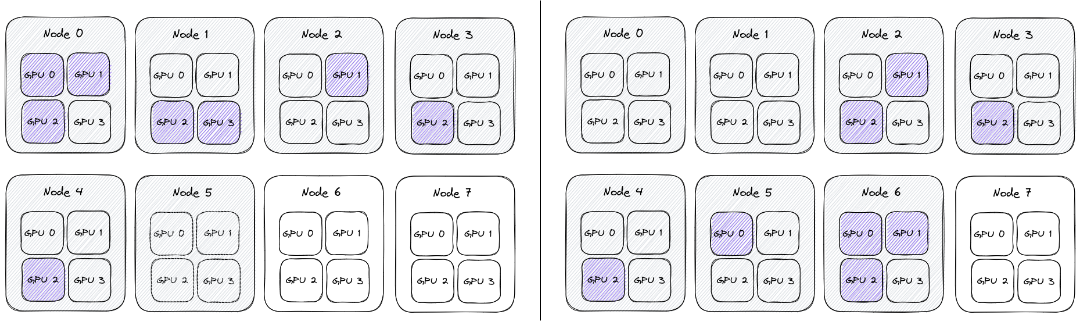

For example, the topologies below can be represented as 3 2 1 1 1 and 0 0 2 1 1 1 3:

Conceptually all the nodes are the same, and the network behaves uniformly between them, so it shouldn’t matter on which node we schedule the training. As a result the topologies above (0 0 2 1 1 1 3 and 3 2 1 1 1) are actually the same, and can be generically represented as 1 1 1 2 3.

Setup

It seems that when deploying Pytorchjobs, the scheduling is only based on availability of the GPUs. Since there isn’t an automatic way to enforce topology at the node level, the topology was captured using the following procedure:

- Identify schedulable nodes. Begin with four available nodes, then increase to five, six, seven, and eight. Workloads will be assigned to available GPUs by the Kubernetes scheduler. Repeat steps 2 through 5 for each available set of nodes.

- On each GPU, clear memory and delete processes.